Assessment

last authored: Sept 2014, David LaPierre

last reviewed:

Introduction

Regular and ongoing assessment is very important during training in health care, playing a role in ongoing professional development and in evaluation.

Assessment is a ‘‘systematic method of obtaining information from [scales] and other sources, used to draw inferences about characteristics of people, objects, or programs,’’ according to the US Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (AERA, APA, & NCME Joint Committee on Standards 1999, p. 272).

Assessment is powerfully motivating for learners, and they will often study and prepare according to what they expect. This can be positive, but also has the potential to be very negative or harmful. If teachers appreciate this influence, and provide a clear link between course objective and assessment tools, students should learn what they need to learn.

Assessment is important during all phases of education:

- during application

- during orientation (needs assessment)

- throughout the educational program (ongoing feedback)

- at the completion of the program (summative assessment to certify competence).

There are a variety of assessment tools, which can be used according to the setting and what they are designed to measure. It is clear that multimodal and multitemporal assessment is important.

New ways of summarizing and aggregating this are needed standardization of assessment is critical.

Roles of Assessment

Assessment plays three main roles during training in health care (Epstein, 2007):

- improving practice of learners and health providers, through motivation and guidance, as well as improving edcuation

- protecting the public from incompetent providers; identifying learners early on who should leave the program

- selecting learners for further training and/or rewards

Very often, unfortunately, assessments are used inappropriately, and as a result, fail to be optimally helpful.

Key roles of competency-based assessment also include:

- ideally, effective assessment will lead away from a dependence on the time-based approach that has characterized medical education to date.

- information about the effective functioning of programs, for quality improvement and for accreditation

- increased confidence of the public in training programs and health providers

David Leach - "That which we measure, we tend to improve"

Summative assessment

When we speak of assessment, the first things that usually comes to mind are evaluations such as tests and exams designed to result in a mark. Assessments of this nature, which lead to decisions regarding advancement or readiness to practice, are termed summative. Because of their importance, summative assessments must represent the judgement of a trainee's performance in relation to clearly defined learning objectives and criteria. Frequently this information is insufficiently provided, leading to anxiety and/or misinformation, for example from previous exams or groups of students (Newbie and Cannon, 2001).

Summative assessment is important periodically to assure that residents are on track for successful completion of the program and to identify faltering or failing residents who need additional or modified educational opportunities or other interventions to address their individual needs.

"It is in the evaluation system that the 'real' objectives of any program are displayed, and the truly important values become apparent." (Neufeld, 1985)

Formative assessment

Assessment can also be formative, meaning it is designed primarily to strengthen the learner's future performance, provide encouragement, or lead to self-reflection. Often this style is informal and confidential. To be maximally helpful, these assessments should be viewed as non-threatening in order to encourage students to reveal, rather than hide, their weaknesses. In doing so, mistakes or gaps can be caught and addressed before they become solidified.

All types of formative assessment results in feedback of some nature, whether it be an emotion or self-reflection; observations from patients, preceptors, or others; or a written or computerized analysis of a test taken. Given the importance of human-human interaction, we use the term feedback to refer specifically to this process. Much more is written about it here.

Objective formative assessments can be very important in helping learners identify and rectify gaps, and have been shown to result in large improvements on evaluation performance (Norman, Neville, Blake, and Mueller, 2010). These significant positive effects on learning can also be accompanied by strong feelings of value by students, even when voluntary (Velan, Jones, McNeil, and Kumar, 2008).

A formative test bank has been established (Hammoud and Barclay, 2002).

Types of Assessment

All assessment tools have strengths and weaknesses, and some types of tools are better than others for a given task (Sherbino, Bandiera, and Frank, 2008). This becomes especially important for high-stakes assessments, eg completion of a program or credentialling, as the appropriate use of quality assessment tools becomes of paramount important. As such, a variety of assessment tools are often used to ensure the range of competencies are indeed being covered; this may be considered an assessment blueprint (Newbie and Cannon, 2001).

The number of questions should reflect the relative importance of the objective.

Some commonly-used types of tools are as follows:

written assessments

|

clinical assessments

quality of care indicators

|

other |

Targets of Assessment

Many aspects of a learner's knowledge, skills, and attitudes can be measured, though "not everything that can be counted counts; not everything that counts can be counted" (best attributed to William Bruce Cameron).

Proposed targets of assessment.

Some of the targets to be assessed include:

- knowledge, acquisition and application

- history and physical exams skills

- clinical reasoning

- quality of care

- teamwork

- practice-based learning

- systems-based practice

- professionalism

- communication

- future performance

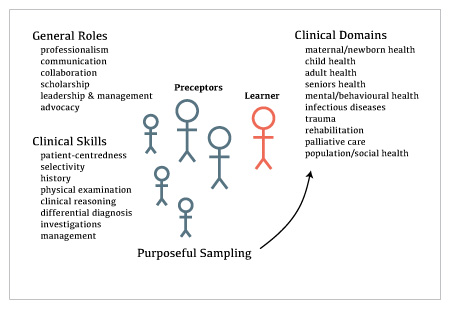

The SiH model takes into account the differing roles of preceptors.

In the figure at right, a small number of preceptors (eg, two) follow the learner over time. This longitudinal relationship allows robust assessment of a number of factors.

A larger number of preceptors, also assist in assessment, though in a more limited way.

Ideally, preceptors are primarily responsible for assessing the general roles and clinical skills identified at left.

The learner's focus should primarily be on ensuring progressive readiness to practice within a given clinical domain. In this figure, the domains are organized according to a hybrid of populations and pathologies. This could be re-assembled in other ways as well, eg body systems or practice environments (eg clinic, emergency department, etc).

Quality of Assessment Tools

see also: quality of assessment tools

It is critical that assessments be viewed by learners and educators as useful. Van der Vleuten (1996) describes five criteria to be used in evaluating assessment:

ReliabilityAssessment results should be consistent, especially in regards to pass/fail measures. |

ValidityAssessment should focus on performance that accurately reflects real life.

|

ImpactAssessment should benefit the learner's trajectory, rather than simply leading to a passing grade.

|

AcceptabilityLearners, preceptors, administration, and the public should all see assessment as meaningful and fair. |

Cost/FeasabilityAssessment should be effective in regards to time, money, and other resources. |

Ideally these factors are all well-accounted for in tool design. "Traditional approaches to measurement, based in the psychometric imperative, have been leery of work-based assessment, given the biases inherent in the clinical setting and the challenges of 'adjusting' for contextual factors that make it difficult to determine the 'true' score, or rating, of comeptence" (Holmboe et al, 2010). As such, the assessment process requires incorporating context.

Assessment should ideally be criterion-based (judged against established standards), rather than normative (judging against one's peers). The rationale for this comes largely from the fact that comparison against other learners often results in standards that are too low (Holmboe et al, 2010). One example from the literature describes central line insertion. In this study, all residents learning the procedure failed the baseline assessment. If normative assessment was used, it could be determined that all the group was competent, whereas in fact none of them were (Barsuk et al, 2009). Conversely, should educators really set out to ensure that some students fail, as occurs with some grading according to a curve?

Criterion-referenced assessment is of fundamental importance in determining competence, particularly in regards to a certain minimum standard. The process leading to this can be challenging for educators, though often leads to increases in assessment validity (Newbie and Cannon, 2001).

When examining competence of students across schools, it becomes clear that nationally agreed upon standards for assessment are very helpful. This should be balanced with the ability of schools or programs to determine their own curriculum and assessment strategies.

In line with this, Holmboe et al (2010) suggest programs need to "move away from developing multiple "home-grown" assessment tools and work instead toward the adoption of a core set of assessment tools that will be used in all programs within a country or region."

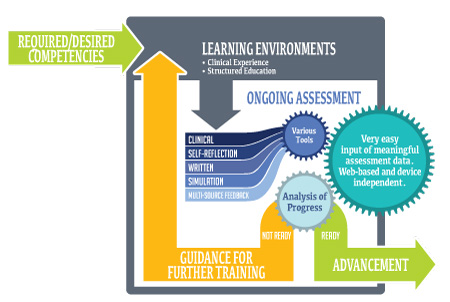

Integration of Assessment

Multimethod assessment makes clear sense, in regards to avoiding limitations of a given type of testing and to derive robust data over time. This is especially true for competency based assessment, which "necessitates a robust and multifaceted assessment system" (Holmboe et al, 2010).

Assessment framework

Assessment involves multiple assessors using multiple tools, interacting with the learner. There are many interactions that therefore are taking place, and these adapt and change over time.

Unfortunately, design and implementation of a system like this has proven extremely challenging.

Our SiH model is to utilize appropriate types of tools to assess various competencies, building in a step-wise fashion.

Assessment and Context

Assessment should take place in a number of clinical contexts, with a balance of complex, real-life situations that require reasoning and judgement with structured, focused assessment of knowledge, skills, and behaviour (Epstein, 2007).

Combining these data is often done in a portfolio.

Pass-fail standards need to be in place to assess appropriate developmental standards (eg benchmarking).

Content specificity: learners may excel in one clinical encounter, eg sore throat, and appear to be functioning at a high level. However, perhaps their knowledge of diabetes care is quite poor; in this case, their performance will also likely be quite poor.

Context specifity: setting also can play a big role in affecting performance. For example, a learner may competently care for a patient with cough in the emergency department, but not the clinic.

"New ways of combining qualitative and quantitative data will be required if portfolio assessments are to find widespread application and withstand the test of time" (Epstein, 2007).

Truly, subjective judgement is present when faculty are assessing learners. However, while training through faculty development is a necessary component, the 'profession' of medicine almost by definition embraces individual clinical judegement.

Entrustment

main article: entrustment

ten Cate and colleagues (2010) have suggested a main goal of assessment in competency-based education is to determine entrustability related to a specific role, in a specific context. There are four main factors contributing to this:

- estimated ability of the resident

- approach and skills of the supervisor

- nature of the EPA

- local circumstances or context, ie location, time of day, emergency setting, etc

Ideally, reliable and valid assessment tools should be used in determining entrustment. To ensure readiness, ideally at least two faculty should observe the learner before judging readiness for practice.

Benchmarking

Even though assessment should be compared against criteria, not peers, it is at the same time important to take into consideration the level of training, or developmental stage, of a learner. Benchmarking, or milestoning, allows determination as to whether the learner's trajectory is on target or not (Green et al, 2009).

Benchmarks can differ in different clinical domains, and learners may progress more or less quickly according to aptitude, prior experience, or interest.

Assessment of Expertise

As competence grows, the task of assessment shifts to higher level cognitive tasks and performance when faced with significant stress and/or ambiguity.

Testing inductive thinking (the use of data to identify possibilities), or deductive thinking (the use of data to deduce the correct response among possibilities) becomes important (Epstein, 2007).

Future Directions

As the assessment continues to evolve, medical educators and researchers need to identify mechanisms of creating and maintaining best practices, especially in the context of systemic and institutional culture (Holmboe et al, 2010).

Threats to Assessment

Lake wobegon effect

There is evidence (where?) suggesting a 5 point likert is more valid than a 3 point

Get this data

IMGs their pass rate is much poorer (Walsh et al, 2011) 90 for CMG vs 50-70

Resources and References

Barsuk JH et al. 2009. Use of simulation-based mastery learning to improve the quality of central venous catheter placement in a medical intensive care unit. J Hosp Med. 4(7):397-403.

Epstein RM. 2007. Assessment in Medical Education. NEJM. 356(4): 387-396.

Green ML et al. 2009. Charting the road to competence: developmental milestones for internal medicine residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 1:5-20.

Hammoud MM, Barclay ML. 2002. Development of a Web-based question database for students' self-assessment. Acad Med. 77(9):925.

Holmboe ES et al. 2010. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Medical Teacher. 32:676-682.

Neufeld VR. 1985. Assessing clinical competence. New York, NY: Springer Publishing: 7.

Newbie D, Cannon R. 2001. Assessing the Students. A handbook for medical teachers. 4th Ed. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, p 125-63.

Norman G, Neville A, Blake JM, Mueller B. 2010. Assessment steers learning down the right road: impact of progress testing on licensing examination performance. Med Teach. 32(6):496-9.

Pangaro L. 1999. Academic Medicine. 74(11): 1203-1207.

Sherbino J, Bandiera G, Frank JR. 2008. Assessing competence in emergency medicine trainees: an overview of effective methodologies. CJEM. 10(4):365-71.

ten Cate O, Snell L, Carraccio C. 2010. Medical competence: the interplay between individual ability and the health care environment. Medical Teacher. 32:669-675.

Van der Vleuten.1996. The assessment of professional competence: developments, research, and practical implications. Adv Health Sci Educ 1:41-67.

Velan GM, Jones P, McNeil HP, Kumar RK. 2008. Integrated online formative assessments in the biomedical sciences for medical students: benefits for learning. 8:52.