Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery

last written: Nov 2011, David LaPierre

last reviewed: Jan 2012, Dorothy Chanda

Introduction

Vaginal delivery of an infant follows labour, the process of regular uterine contractions leading to the birth of the infant and the placenta. This topic describes the mechanisms of an uncomplicated vaginal delivery, and the involvement of a skilled health care professional in ensuring outcomes for the mother and child are optimized.

Labour is described in a separate topic here.

Mechanisms of Labour, by Erin Chia

Different health providers approach delivery in different ways. Many physicians take an active role in guiding the infant out, in the interests of minimizing trauma to the birth canal.

Others take a much more 'hands-off' approach. In most centres, routine episiotomy is no longer used, and some allow the mother and baby to accomplish the work of delivery with very little guidance.

Regardless of the steps taken, care is required to maintain a low risk of infection to mother and baby.

While the majority of deliveries are joyful and otherwise uneventful, there are a few true emergencies, including shoulder dystocia, postpartum hemorrhage, and neonatal apnea that can quickly arise. It is critical for the health care team to regularly practice and be prepared for these situations.

There are many ways of learning how to deliver an infant; we recommend praticing with a Laerdal MamaNatalie trainer, available for use in low-resource settings.

Supplies Required

Instruments for delivery:

- soap

- sterile gloves, surgical drapes

- effective lighting

- clamps/sterile string, scalpel for the umbilical cord

- suture material and local anaesthetic

- gauze

- oxytocin/misoprostol

- IV supplies

- newborn supplies: suction, bag-valve mask, oxygen

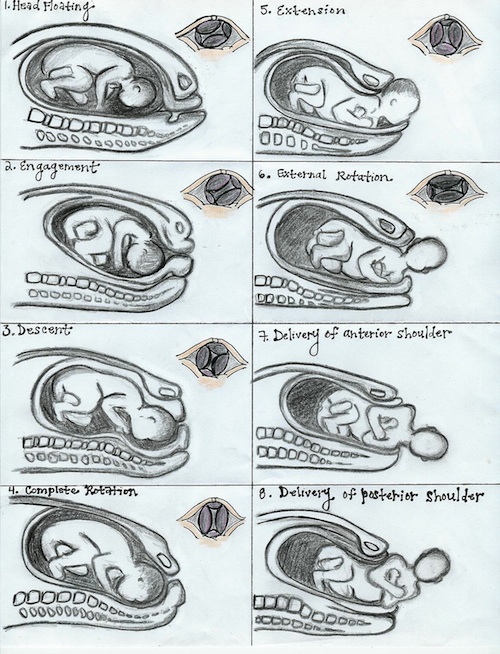

Cardinal Mechanisms of Labour

Mechanism |

What Should be Done |

Engagement is the descent of the widest part of the fetus through the pelvic inlet. This normally occurs 2-3 weeks before labour in nulliparous women and may occur any time before or after onset of labour in multiparous women. |

|

Descent occurs prior to onset and then throughout labour. The other mechanisms superimposed on it. Descent occurs at greater rate during latter part of the 1st stage and 2nd stage. It is brought about by pressure of the amniotic fluid, pressure from the uterus on the fetus, maternal efforts of bearing down, and elongation of the fetus. |

Monitor cervical change throughout labour, as described here.

|

Flexion is the movement of the chin towards to thorax, and is important to optimize the presenting diameter of the head. It is present before labour to some degree due to natural muscle tone. It is further encouraged during labour by resistance from cervix, walls of pelvis, and pelvic floor. |

|

Internal Rotation occurs as the head descends through the pelvis in the majority of cases. Normally the occiput is turned towards symphysis pubis (OA, occiput anterior position), but in approximately 20% of cases, the head rotates occiput posterior (OP). |

Some providers will gently stretch the perineum. Other providers adopt a 'hands off' approach, citing evidence that massage does not improve outcomes (Stamp et al, 2011). This may also be a good time to offer a pudendal block. |

Extension occurs with progression of the head to the vulva. Pressure from the uterus acts posteriorly, and pressure from the symphysis acts anteriorly. These combine to produce a main force in the direction of the vaginal opening. The head progressively stretches the perineum and vaginal opening, and the occiput, forehead, nose, and chin progressively pass through. Crowning occurs as the maximal head circumference is present at the vaginal opening. Once the chin is delivered, the head drops downward. |

Advise the mother to push gently as the head crowns. Some providers will support the perineum with one hand and maintain the head in flexion, often using a warm towel. This is to slow the head and reduce the likelihood of significant tears. As above, other providers prefer not to support the perineum at this point. Evidence on which is superior is equivocal (McCandlish et al, 1998). |

External Rotation/Restitution follows rotation of the occiput to the left or right, as was originally present, with the head realigned with the back and shoulders. One shoulder is behind the symphysis and the other posterior. |

Allow the head to restitute on it's own.

|

Expulsion occurs as the anterior shoulder moves under the symphysis and through the vaginal opening. The posterior shoulder follows, and the rest of the body quickly passes behind. |

Gentle downwards pressure can be used to first deliver the anterior shoulder. The posterior shoulder will soon follow. Securely hold the infant and place it on the mother's abdomen, assessing for need for recuscitation. Many providers give IM or IV oxytocin with the delivery of the anterior shoulder to reduce the likelihood of postpartum hemorrhage. |

Cord Clamping

Cord clamping should be performed under sterile conditions, using either clamps or string and a razor or scissors. It is clear that sterile conditions reduce infection risk to the infant.

In many facilities it is routine to immediately clamp the cord to facilitate the delivery of the placenta and to free the infant in situations where resuscitation is required. In contrast to this existing practice, increasing evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping for at least 3 min is safe for mother and child, does not increase risk of jaundice, and can reduce the risk of iron deficiency of the infant through transfusion of placental blood (Andersson O et al, 2011).

Placental Delivery

Delivery of the placenta is included with the third stage of labour. Signs of placental separation from the uterine wall include:

- gush of blood from vagina

- umbilical cord lengthening

- fundus of uterus moves up into abdomen

- uterus becomes firm and globular

Active management describes several interventions that are designed to facilitate the delivery of the placenta by increasing contractions and preventing uterine atony, decreasing the risk of hemorrhage. It should be offered to all women. If physiological management is used (no intervention to shorten the duration of the third stage), the placenta usually separates from the uterus and is delivered within 30 minutes, and when active management is used, the mean time to delivery is 8 minutes.

The clinical significance of active management includes (Prendiville, Elbourne, McDonald, 2000):

- approximately 60% reduction in the occurrence of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) greater than or equal to 500 mL and 1000 mL, hemoglobin value of less than 9 g/dL at 24-48 hours after delivery, and the need for blood transfusion

- 80% reduced need for therapeutic uterotonic agents

- for every 12 patients receiving active rather than physiological management, 1 PPH is prevented

- for every 67 patients with active management, 1 would avoid transfusion with blood products

Potential Risks/ Disadvantages of Active Management include (Prendiville, Elbourne, McDonald, 2000, Smith 2015):

- pain at injection site if uterotonic is given IM

- nausea and vomiting and elevated blood pressure associated with ergometrine

- endangering undiagnosed twin by encouraging placental separation

- increasing risk of uterine inversion by pulling on the cord while placenta is still attached

- increased afterpains for multiparous women

Components of Active management include:

1) Administration of oxytocin within one minute of delivery (often with the delivery of the anterior shoulder); may be given IM or IV

- alternatives to oxytocin include ergometrine IM, Syntometrine IM (both contraindicated with hypertension), misoprostol orally

2) Controlled cord traction (CCT). Steps include:

- Clamp cord close to perineum (once pulsation stops or you have clamped and cut the cord) and hold in one hand

- Stabilize uterus with other hand, applying counter pressure

- Keep slight tension on cord and wait for a strong contraction (2-3 mins)

- Tell mother to push and pull gently on cord in downwards motion with the contraction

- If placenta doesn’t descend during 30-40 seconds of CCT, don’t keep pulling

- Wait for another contraction, then repeat with counter pressure

3) Uterine massage after delivery of placenta

- Immediately massage fundus of uterus until well contracted

- Palpate for contracted uterus q 15 mins

If phyioslogical management is used instead of active management, do not pull on the cord! The placenta should only be delivered using maternal pushing efforts. CCT should not be used prematurely due to concern of uterine inversion.

Make sure to inspect the placenta to ensure complete removal of all cotyledons and membrane.

Remaining Steps

Encourage skin-on-skin contact between mother and infant, as well as breastfeeding, if there are no concerns regarding the infant.

Inspect cervix, vagina, and perineum for lacerations and repair if necessary, as described here. Watch closely for signs of postpartum hemorrhage.

Cord gases should be obtained if diagnostic capacity allows. A newborn exam can be deferred if the infant appears healthy.

Resources and References

Andersson O et al. 2011. Effect of delayed versus early umbilical cord clamping on neonatal outcomes and iron status at 4 months: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 343.

McCandlish R et al. 1998. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 105(12):1262-72.

Nothnagle M, Scott Taylor J. 2003 May. Should Active Management of the Third Stage of Labor be Routine? Am Fam Physician. 15;67(10):2119-2120

Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonald S. 2000. Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD000007. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000007.

Smith J. 2015. Management of the Third Stage of Labour. Medscape.

Stamp G, Kruzins G, Crowther C. 2001. Perineal massage in labour and prevention of perineal trauma: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 322(7297):1277-80.

Steer P and Flint C. 1999. ABC of labour care Physiology and management of normal labour. BMJ. 318(7186): 793–796.