Endometrial Cancer

last authored: Sept 2010, David LaPierre

last reviewed: Nov 2010, Melissa Vyvey

Introduction

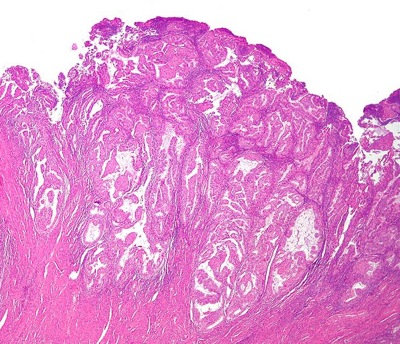

Endometrial adenocarcinoma, low magnification

courtesy of Nephron

Endometrial cancer, or cancer of the uterus, is the commonest malignancy of the female genital tract in North America, making it the 4th-most common cancer in women in the US. The median age at diagnosis is within the sixth decade of life, but 20-25% of cases will be diagnosed in pre-menopausal women.

It often presents early via vaginal bleeding, and as such is frequently diagnosed at an early stage, when survival is good. Abnormal vaginal bleeding in perimenoapusal and post-menopausal women is attributable to endometrial cancer in about 10% of cases.

Vaginal bleeding in a postmenopausal woman, and any abnormal vaginal bleeding with no other apparent cause, should be vigorously investigated for the possibility of endometrial cancer.

Endometrial hyperplasia is a precursor to endometrial cancer and also requires aggressive management.

The Case of Jane Welton

Jane is a 56 year-old woman who goes to her family doctor with spotting she has noticed in her underwear over the past week.

- What should her family doctor ask her?

- What is the differential diagnosis of postmenopausal bleeding?

- What investigations, if any, should be done?

Causes and Risk Factors

Endometrial cancer is caused principally by unopposed high estrogen levels, most commonly as a result of obesity. Indeed, being 50 lbs overweight represents a 10 times increased risk.

Other risk factors include:

- nulliparity

- early menarche

- menopause >age 52

- diabetes

- PCOS (chronic anovulation)

- estrogen-secreting tumour

- unopposed estrogen hormone replacement therapy (i.e. not giving progesterone as well as estrogen, or not giving enough progesterone, to a post-menopausal woman with an intact uterus)

- tamoxifen treatment

- Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colon Cancer (HNPCC or Lynch Syndrome) on family history

factors that decrease risk include:

- ovulation

- OCP

- progestin

- menopause <49

- normal weight

- multiparity

- smoking

Pathophysiology

Endometrial hyperplasia is a precursor to endometrial cancer, and is also caused by unopposed estrogen. In 5-25% of cases, atypical endometrial hyperplasia will progress to endometrial cancer, and in 20% of women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia there is coexisting endometrial cancer.

Various histologic subtypes include:

- endometroid adenocarcinoma (most common; good prognosis)

- villoglandular adenocarcinoma

- adenocarcinoma

- clear cell adenocarcinoma

- mucinous adenocarcinoma

- uterine papillary serous adenocarcinoma

- squamous cell carcinoma

- undifferentiated carcinoma

- malignant mixed mesodermal carcinoma

Signs and Symptoms

- history

- physical exam

History

Postmenopausal bleeding is endometrial cancer until proven otherwise. Premenopausal women with this condition may have heavy bleeding during periods, or bleeding between periods.

Other important aspects of the history include:

Menstrual history

- age at menarche

- duration and severity of menstrual flow

- menopause

Past medical history

- diabetes

- breast cancer, tamoxifen use

Family history

- breast cancer

- colon cancer

- ovarian cancer

- uterine cancer

Functional Inquiry

- weight loss or gain

- GI symptoms

- genitourinary symptoms

Physical Exam

Abdominal exam

- masses, hepatomegaly

Pelvic exam

- bimanual exam for uterine size, shape, mobility, and tenderness

- rectovaginal exam for mass

- speculum exam to rule out other causes of vaginal bleeding, such as cervical polyp

Lymph node exam

Investigations

- lab investigations

- diagnostic imaging

- surgical staging

Lab Investigations

Endometrial biopsy is the principle modality for diagnosis. This is a procedure that can be done safely and effectively in the office. See this video from the New England Journal of Medicine to learn how to do an endometrial biopsy.

Hysteroscopic biopsy may also be done if endometrial biopsy is negative but suspicion remains.

Pap tests are not effective for detecting endometrial cells, but should be done to rule out cervical dysplasia as a cause of abnormal bleeding.

Swabs for gonorrhea and Chlamydia should be done to rule out infection as a cause of abnormal uterine bleeding.

CA 125 is not helpful for screening or diagnosis, but may be used to follow response to treatment. A high CA 125 value may indicate metastases.

Diagnostic Imaging

A transvaginal ultrasound can be done to determine the endometrial echo, which is the endometrial thickness. In a post-menopausal woman, an endometrial echo of <5mm is normal and anything >5mm requires investigation. In a peri-menopausal or pre-menopausal woman, the transvaginal ultrasound should be done one day 5-8 of the woman’s cycle when the endometrial lining is at its thinnest.

A saline-infusion sonohystogram can be done when there is suspicion that abnormal uterine bleeding may be caused by an endometrial polyp. Saline is infused through the cervix to fill the uterine cavity. This allows for full visualization of the polp, which cannot be easily delineated on regular transvaginal ultrasound, and typically leads to surgical removal.

Surgical Staging

When endometrial cancer has been detected, imaging is not required to stage the cancer, except for a chest x-ray. Staging is done by examination and biopsy of the lymph nodes during surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes:

- endometrial hyperplasia

- atrophic endometritis

- endometrial/cervical polyps

- cervical cancer

- uterine sarcoma

Treatments

Surgery/Radiation/Chemotherapy

Surgery is the primary modality. Vaginal surgery and laparoscopy are options, always with intraoperative assessment of lymph nodes. Depending on staging during surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation may be necessary post-operatively.

Endometrial cancer is staged using the FIGO 2010 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Classification System:

- IA: Tumor confined to the uterus, no or < ½ myometrial invasion

- IB: Tumor confined to the uterus, > ½ myometrial invasion

- II: Cervical stromal invasion, but not beyond uterus

- IIIA: Tumor invades serosa or adnexa

- IIIB: Vaginal and/or parametrial involvement

- IIIC1: Pelvic node involvement

- IIIC2: Para-aortic involvement

- IVA: Tumor invasion bladder and/or bowel mucosa

- IVB: Distant metastases including abdominal metastases and/or inguinal lymph nodes

Surgery alone is sufficient treatment for women with stage 1A or 1B disease.

Medications

Progestin therapy may be used in women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia or very early stage cancer who deeply desire to have children. Optimal dose and prognosis is not clear, though these women should be closely monitored.

Follow-up

The risk of recurrence of endometrial cancer is greatest within the first three years after initial diagnosis. 70% of women will have symptoms with recurrence, so a thorough history is important. The evidence is not strong to support any particular surveillance strategy. In particular, there is little evidence to support any imaging in detecting recurrence.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends that patients should have pelvic exam 3-4 times yearly for at least 5 years. For the first two years, cervical cytology should be done every 6 months. At each visit, CA 125 and chest x-ray are optional. Imaging should only be done as guided by symptoms.

Consequences and Course

Survival depends on stage, as well as grade and histologic type. Survival at five years ranging from over 90% for stage I and ~20% for stage IV.

Resources and References

Canavan TP, Doshi NR. 1999. Endometrial Cancer American Family Physician. 61(5):1369-76.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines

Pecorelli, S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009; 105:103.

Topic Development

authors: David LaPierre, Sept 2010

reviewers: Melissa Vyvey, Nov 2010