Dyslipidemia

last authored: Feb 2011, David LaPierre

last reviewed:

Introduction

blood (left for 4h) from patient with

LDL >40 mmol/L (markedly abnormal)

used with permission, Mark Shea

A typical North Americal diet includes 50-120g of fat, mainly triglycerides, daily, and of this, approximately 400-500 mg of cholesterol.

While dyslipidemia can refer to any abnormality of lipids, or fats, in the blood, it usually is associated with elevated levels of cholesterol and triglycerides. Of these, LDL, or low-density lipoprotein, appears to be the most significant in terms of risk. HDL, or high-density lipoprotein, is a protective molecule, removing harmful plaques from the vasculature.

Dyslipidemia, along with other risk factors such as smoking and hypertension, can cause atherosclerosis, or accumulation of plaques within arteries. This, in turn, can predispose for coronary artery disease and peripheral artery disease, leading to myocardial infarction, stroke, and other serious health issues.

Accordingly, lowering lipid levels in the right populations is an important goal of primary health care. It is important to understand the rationale for screening for, and treating, dyslipidemia - an inexact science that is constantly changing.

The Case of Albert G.

Albert is a 38 year-old man who comes into your office asking you to check his cholesterol, as he has been hearing a great deal about it in the news. You decide to proceed and check it, and the results come back as LDL 3.4 mmol/L, TC/HDL 4.5.

- should you have checked it?

- what, if anything, do you use to treat him?

Causes and Risk Factors

Causes of dyslipidemia that should be ruled out include:

elevated LDL

|

reduced HDL

|

high triglycerides

|

There are many genetic causes for dyslipidemias, beyond the scope of this article.

Pathophysiology

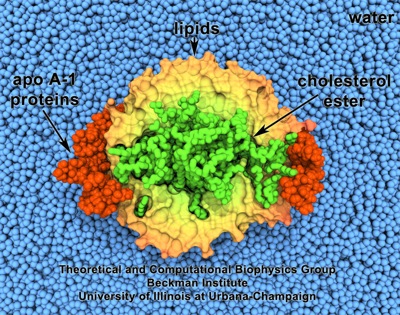

HDL. Made with VMD and owned by the Theoretical & Computational

Biophysics Group, Beckman Institute, University of Illinois,

Urbana-Champaign (more images)

main article: atherosclerosis

Most evidence examining atherosclerosis specifically implicates low density lipoprotein (LDL), the resulting 'metabolic garbage' of liver lipid metabolism. Most LDL is cleared by binding of surface apo B to LDL receptors in many tissues, especially the liver. However, it can also become lodged in vascular walls, inducing plaque development, even if other risk factors are absent.

VLDL and IDL are also involved in transporting cholesterol to the tissues.

High density lipoprotein (HDL), in contrast, is believed to mobilize cholesterol from developing and existing atheromas and transport it to the liver for excretion in the bile.

Signs and Symptoms

Dyslipidemia itself does not cause any signs or symptoms. However, a thorough history and physical exam is necessary for patients in whom it is suspected.

- history

- physical exam

History

As described below, risk factors are important for screening for, and treating, dyslipidemia.

Inquire into:

- history of coronary artery disease: angina, myocardial infarction, CABG, or PCA

- diabetes mellitus

- other vascular disease: aortic aneurysm, peripheral artery disease, stoke, TIA

family history of premature coronary disease in a first-degree relative (<55 in men, <65 in women)

cigarette smoking

alcohol intake

Physical Exam

Height, weight, BMI, waist circumference

Vitals: HR, blood pressure (both arms), ankle-brachial index

Cardiac exam, respiratory exams to assess for coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure

Abdominal exam: rule out obvious liver disease

Signs of atherosclerosis:

- carotid bruit

- renal bruit

- ankle-brachial index <.9

Signs of hyperlipidemia can be seen on physical exam, and include:

- xanthoma - plaques or nodules in skin, especially eyelids: composed of lipid-laden histiocytes

- tendinous xanthoma - lipid deposits in tendon: especially Achilles

- corneal arcus (arcus senilus) - lipid deposit in cornea

Investigations

- screening

- lab investigations

- diagnostic imaging

Screening

Plasma lipid profile should be screened in a number of higher-risk populations. This includes:

Canadian Cardiovascular Society (2009)

all patients with:

|

US National Cholesterol Education Program

|

Lab Investigations

Lipid profile includes:

- fasting total cholesterol

- LDL

- HDL

- triglycerides

Ideally, screening is done after a 12 hour faster, with no alcohol consumed within 48 hours.

The Friedewald formula for calculating LDL: total cholesterol - HDL - triglycerides/5. If triglycerides are >400mg/dL, the results for LDL will be inaccurate. Ask for a direct LDL cholesterol measurement, and ensure the patient is fasting.

hs-CRP may be warranted if patients are moderate risk (see below) and LDL is <3.5 mmol/L. It should be drawn during a time free from acute illness, and the lower of two values, taken at least two weeks apart, should be used.

Other bloodwork to be considered includes:

- serum fasting glucose

- TSH (to assess for hypothyroidism causing dyslipidemia)

- ALT, AST, creatinine(to assess for underlying liver and kidney dysfunction, and to monitor for adverse effects of treatment)

- creatine kinase (to assess for statin-induced myalgias)

Diagnostic Imaging

Imaging may reveal signs of atherosclerosis, including:

- exercise stress testing (though many false postitives and false negatives)

- stress echocardiography

- coronary angiography

- carotid ultrasonography/angiography

- peripheral arterial ultrasound

Risk Assessment

There are a number of clinical calculators for calculating 10-year risk of CVD. These include:

- Framingham Risk Score (FRS) in mmol/L and in mg/dL

- Reynolds Risk Score (RRS); validated in American populations

- UKPDS risk engine (diabetes)

- Australian CVD risk calculator

There are many other risk factors associated with increased rates of CAD, though these do not appear to have an impact on treatment outcomes. Given this, however, it is wise to use clinical judgement when placing patients in risk strata. For example, consider moving patients into high-risk due to metabolic syndrome. As well, a family history of premature CAD increases risk by 1.7x in women and 2.0x in men (Genest et al, 2009). If south Asian (eg India, Pakistan)

High-Risk

|

Medium-Risk

|

Low-Risk

|

Management of Dyslipidemia

- target levels

- lifestyle modification

- medications

Target Levels

There is much debate over ideal treatment targets, though all agree risk level has a substantial impact on decision to treat. According to Canadian Guidelines, LDL is the primary target, with apoB the alternate (Genest et al, 2009). In fact, apoB may be a better marker, given its accuracy. It's target value is less than 0.8 g/L.

Cost-effectiveness of primary prevention strategies is important to consider.

Primary Targets

risk category |

initiate treatment if LDL is: (mmol/L, mg/dL) |

target LDL |

ratio total/HDL |

high (10 yr risk >20%) |

>2.0, >100 |

< 2 mmol/L, or >50% decrease |

>4 |

medium (10 yr risk 10-19%) |

>3.5, >130 |

< 2 mmol/L, or >50% decrease |

>5 |

low (10 yr risk <10%) |

>5.0, >130 with 2 or more risk factors, >160 with 0-1 risk factors |

>50% decrease

|

>6 |

Secondary Targets

trigycerides are a secondary target, after LDL.

- normal: <150 mg/dL

- borderline: 150-199 mg/dL

- high: 200-499 mg/dL

- very high >500 mg/dL

hs-CRP is another secondary target, and may be especially useful in risk stratification in men over 50 or women over 60 at intermediate risk, according to the FRS. Treatment of LDL <3.5 mmol/L appears to be beneficial if the value is >2.0 mg/L, according to Canadian guidelines and the JUPITER study (Ridker et al, 2008).

It correlates with favourable response to statin therapy. Caution should be taken, however, as CRP rises with acute illness. Two readings are therefore advisable.

Other secondary targets include:

- total cholesterol:HDL

- hs-CRP

- non-HDL cholesterol (total cholesterol - HDL cholesterol)

- apoB to apoAI ratio

Clinical evidence is viewed by many to be lacking in regards to these secondary targets.

HDL should be >40 mg/dL.

If dyslipidemia is found, screen for secondary causes, including

Lifestyle Modification

"Clinicians should exercise judgement to avoid premature or unnecessary implementation of lipid-lowering therapy. Health behaviour interventions will have and important long-term impact on health and the long-term effects of pharmacotherapy must be weighted against the potential side effects" (Genest et al, 2009).

All patients should be advised regarding diet, exercise, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption. Lifestyle approaches should be taken for at least 3 months before considering drug therapy.

Smoking

Smoking cessation is perhaps the most important behaviour change for the prevention of CVD, and all available means should be offered patients to assist them.

Diet

High dietary intake of cholesterol and animal fats raises plasma cholesterol levels, while a low ratio of staurated-to-unsaturated fats lowers them.

- <25% of calories should be from fat, less than 7% of calories should be from saturated fat

- avoid trans fats

- less than 200 mg of cholesterol/day

- increase fruits, vegetables, and dietary fibre

- polyunsaturated fats: up to 10% of calories

- monounsaturated fats: up to 20% of calories

- omega-3 fatty acids seem particularly beneficial

Exercise

Aerobic exercise is recommended for at least 30 min/day, on most, if not all, days of the week. This helps prevent CVD, and improve diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL.

Alcohol

Alcohol intake is permissible if not in excess (one drink daily for women, and two or less daily for men), and if no contraindications (such as alcoholism) are present. In fact, moderate alcohol intake can increase HDL levels.

Stress

Stress and depression is an important cardiac risk factor and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Lichtman et al, 2008). Effective diagnosis and treatment is important for patients at increased risk of, or with, CVD.

Medications

In high-risk patients, medications should be offered immediately, as there is a 20-25% lowering in CVD mortality and nonfatal MI with every 1.0 mmol/L decrease in LDL, according to a 2005 meta-analysis (Baigent et al, 2005).

Statins are the first line treatment. Other medications may need to be added to statins, or in place of them if indicated.

Statins

Statins act by decreasing cholesterol production and increase LDL uptake. They are usually well-tolerated, but can cause myalgias in approximately 5% of users. These are dull muscle aches, often worse with exercise, and serum CK levels often remain normal. Withdrawal and re-challenge can make the diagnosis. Pravastatin is one of the best tolerated.

Myositis can also occur, with damage to muscles causing CK release. This can be dangerous, prompting dose reduction or cessation.

Rhabdomyolysis is rare but can be life-threatening. This is characterized by severe pain, CK over 10,000 U/L, myoglobinuria, and potential renal failure. It should prompt hospitalization for treatment.

Hepatotoxicity can occur in up to 2% of patients.

After initiating drug therapy, lipids should be measured at 6 weeks and 3 months. Monitor ALT, AST, and CK at baseline, three months after a dose adjustment, and every 6-12 months thereafter.

Niacin

Niacin, or nicotinic acid, is a vitamin which lowers VLDL synthesis in the liver. It can decrease levels of LDL and triglycerides, while raising HDL by 15-25%.

Side effects of niacin include flushing, dry skin, gastritis, and poorer glycemic control in patients with diabetes. ASA taken beforehand can attenuate flushing. Hepatotoxicity may increase with use of statin + niacin, necessitating regular assessment of transaminases.

ALT should be measured at baseline and after 1-3 months. Fasting blood glucose should be assessed every 6-12 months, as niacin can increase blood glucose.

Ezitimibe

Ezetimibe inhibits cholesterol absorption in the gut. It is frequently used in combination with statins to decrease LDL.

Bile Acid Resins

Cholestyramine and colestipol inhibit bile acid reabsorption. They may be used with statin combination therapy.

Fibrates

Fibrates (bezafibrate, fenofibrate, gembrozil) are excellent at lowering triglycerides by increasing peripheral lipolysis and decreasing hepatic TAG production. They only modestly increase HDL.

They should be used as first-line in patients with marked hypertriglyceridemia (>10 mmol/L) to prevent pancreatitis. In patients with moderate levels (5-10 mmol/L), fibrates may be used, though the impact on prevention of CVD is unclear.

Fibrates may be used in combination with statins, but this can increase serum creatinine, requiring monitoring of kidney function. Gembrozil should not be used with statins due to increased risk of rhabdomyolysis.

An expert should be consulted if you suspect an underlying disorder due to the following: positive family history for genetic conditions, very low HDL, or very high triglycerides. Referral may also be considered in cases of drug intolerance, lack of response, or unexplained atherosclerosis.

Consequences and Course

As discussed, the primary concern for patients with dyslipidemia is cardiovascular disease through atherosclerosis, including coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral artery disease.

Hypertriglyceridemia can cause acute pancreatitis.

Resources and References

Baigent C et al. 2005. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 366:1267-78.

Genest J et al. 2009. 2009 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult - 2009 recommendations. Can J Cardiol. 25(10):567-79.

Lichtman JH et al. 2008. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 118(17):1768-75.

McPherson R et al. 2006. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement--recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 22(11):913-27.

Topic Development

authors: David LaPierre, 2011

reviewers: