Large Intestine

last authored:

last reviewed:

Introduction

The large intestine is the terminal part of the gastrointestinal tract. The primary function of this organ is to finish absorption of water, electrolytes, and other nutrients, synthesize certain vitamins, and to form and store wastes before defecation. Normal stool weight is 100-150 g/day.

The large intestine runs from the appendix to the anus. Surrounding the small intestine, which is twice as long as the large intestine, it has a diameter of approximaely 3 inches.

Anatomy

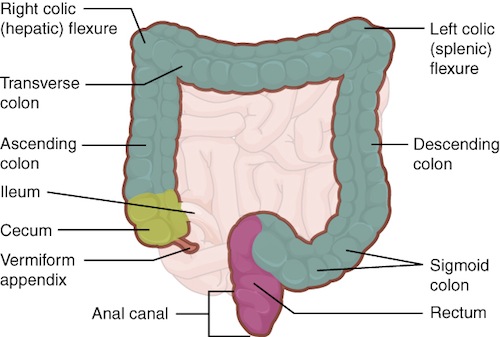

The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: the cecum, the colon, the rectum, and the anus. The ascending colon, descending colon, and the rectum are all located in the retroperitoneum. However, the transverse colon and sigmoid colon are surrounded by mesocolon, and are therefore located within the peritoneum.

Cecum and colon

The first part of the large intestine is the cecum, a sac-like structure about 6 cm (2.4 in) long. Chyme passes ileum of the small intestine, throough the ileocecal valve, and enters the large intestine. The cecum blends seamlessly with the colon.

Upon entering the colon, the food residue first travels up the ascending colon on the right side of the abdomen. At the inferior surface of the liver, the colon bends to form the right colic flexure (hepatic flexure) and becomes the transverse colon. The region defined as hindgut begins with the last third of the transverse colon and continues on. Food residue passing through the transverse colon travels across to the left side of the abdomen, where the colon angles sharply immediately inferior to the spleen, at the left colic flexure (splenic flexure). From there, food residue passes through the descending colon, which runs down the left side of the posterior abdominal wall. After entering the pelvis, it becomes the s-shaped sigmoid colon, which extends to the midline to end in the rectum.

Appendix

The appendix (or vermiform appendix) is a winding tube that attaches to the cecum. Although the 7.6-cm (3-in) long appendix contains lymphoid tissue, suggesting an immunologic function, this organ is generally considered vestigial. However, at least one recent report postulates a survival advantage conferred by the appendix: In diarrheal illness, the appendix may serve as a bacterial reservoir to repopulate the enteric bacteria for those surviving the initial phases of the illness. Moreover, its twisted anatomy provides a haven for the accumulation and multiplication of enteric bacteria. The mesoappendix, the mesentery of the appendix, tethers it to the mesentery of the ileum.

Rectum

Food residue leaving the sigmoid colon enters the rectum in the pelvis, near the third sacral vertebra. The final 20.3 cm (8 in) of the alimentary canal, the rectum extends anterior to the sacrum and coccyx. Even though rectum is Latin for “straight,” this structure follows the curved contour of the sacrum and has three lateral bends that create a trio of internal transverse folds called the rectal valves. These valves help separate the feces from gas to prevent the simultaneous passage of feces and gas.

Anus

Finally, food residue reaches the last part of the large intestine, the anal canal, which is located in the perineum, completely outside of the abdominopelvic cavity. This 3.8–5 cm (1.5–2 in) long structure opens to the exterior of the body at the anus. The anal canal includes two sphincters. The internal anal sphincter is made of smooth muscle, and its contractions are involuntary. The external anal sphincter is made of skeletal muscle, which is under voluntary control. Except when defecating, both usually remain closed.

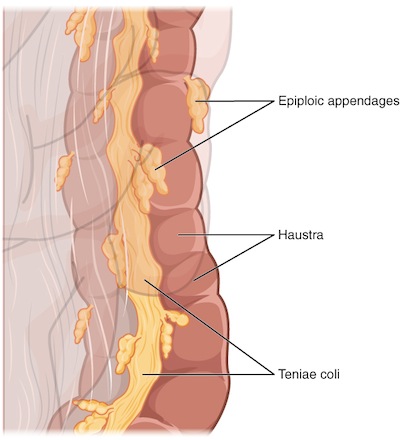

Three features are unique to the large intestine: teniae coli, haustra, and epiploic appendages. The teniae coli are three bands of smooth muscle that make up the longitudinal muscle layer of the muscularis of the large intestine, except at its terminal end.

Tonic contractions of the teniae coli bunch up the colon into a succession of pouches called haustra (singular = hostrum), which are responsible for the wrinkled appearance of the colon.

Attached to the teniae coli are small, fat-filled sacs of visceral peritoneum called epiploic appendages. The purpose of these is unknown. Although the rectum and anal canal have neither teniae coli nor haustra, they do have well-developed layers of muscularis that create the strong contractions needed for defecation.

Colon flora

There are over 700 types of bacteria in the colon, numbering in the trillions and with a combined weight of over 1 kg (ref). These are bacteria that reside long-term, as most bacteria that enter the stomach are killed by lysozyme, defensins, HCl, or protein-digesting enzymes.

These bacteria include:

- anaerobes

- coliforms

- enterococci

Most of these bacteria are nonpathogenic commensal organisms that cause no harm as long as they stay in the gut lumen. In fact, many facilitate chemical digestion and absorption, and some synthesize certain vitamins, mainly biotin, pantothenic acid, and vitamin K. Some are linked to increased immune response.

A refined system prevents these bacteria from crossing the mucosal barrier. Dendritic cells monitor the mucosa and present antigens to T cells in neighbouring lymphoid follicles. If necessary, an IgA-mediated response can trigger local immune activation.

Digestion in the Colon

The residue of chyme that enters the large intestine contains few nutrients except water, which is reabsorbed as the residue lingers in the large intestine, typically for 12 to 24 hours. The large intestine can be completely removed without significantly affecting digestive functioning.

In the large intestine, mechanical digestion begins when chyme moves from the ileum into the cecum, an activity regulated by the ileocecal sphincter. After eating, peristalsis in the ileum forces chyme into the cecum. When the cecum is distended with chyme, contractions of the ileocecal sphincter strengthen. Once chyme enters the cecum, colon movements begin.

Mechanical digestion in the large intestine includes a combination of three types of movements. The presence of food residues in the colon stimulates a slow-moving haustral contraction. This type of movement involves sluggish segmentation, primarily in the transverse and descending colons. When a haustrum is distended with chyme, its muscle contracts, pushing the residue into the next haustrum. These contractions occur about every 30 minutes, and each last about 1 minute. These movements also mix the food residue, which helps the large intestine absorb water.

The second type of movement is peristalsis, which, in the large intestine, is slower than in the more proximal portions of the alimentary canal.

The third type is a mass movement. These strong waves start midway through the transverse colon and quickly force the contents toward the rectum. Mass movements usually occur three or four times per day, either while you eat or immediately afterward. Distension in the stomach and the breakdown products of digestion in the small intestine provoke the gastrocolic reflex, which increases motility, including mass movements, in the colon. Fiber in the diet both softens the stool and increases the power of colonic contractions, optimizing the activities of the colon.

Although the glands of the large intestine secrete mucus, they do not secrete digestive enzymes. Therefore, chemical digestion in the large intestine occurs exclusively because of bacteria in the lumen of the colon. Through the process of saccharolytic fermentation, bacteria break down some of the remaining carbohydrates. This results in the discharge of hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane gases that create flatus (gas) in the colon; flatulence is excessive flatus. Each day, up to 1500 mL of flatus is produced in the colon. More is produced from foods such as beans with indigestible sugars and complex carbohydrates like soluble dietary fiber.

The small intestine absorbs about 90 percent of the water you ingest (either as liquid or within solid food). The large intestine absorbs most of the remaining water, a process that converts the liquid chyme residue into semisolid feces (“stool”). Feces is composed of undigested food residues, unabsorbed digested substances, millions of bacteria, old epithelial cells from the GI mucosa, inorganic salts, and enough water to let it pass smoothly out of the body. Of every 500 mL (17 ounces) of food residue that enters the cecum each day, about 150 mL (5 ounces) become feces.

Feces are eliminated through contractions of the rectal muscles, described further under defecation.

Cell Biology

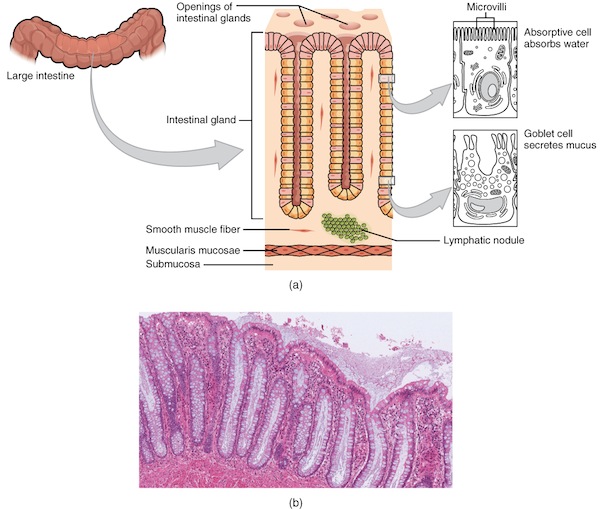

Courtsey of a) OpenStax College, Anatomy and Physiology, and b) University of Michigan

There are several notable differences between the walls of the large and small intestines. For example, few enzyme-secreting cells are found in the wall of the large intestine, and there are no circular folds or villi. Other than in the anal canal, the mucosa of the colon is simple columnar epithelium made mostly of enterocytes (absorptive cells) and goblet cells. In addition, the wall of the large intestine has far more intestinal glands, which contain a vast population of enterocytes and goblet cells. These goblet cells secrete mucus that eases the movement of feces and protects the intestine from the effects of the acids and gases produced by enteric bacteria. The enterocytes absorb water and salts as well as vitamins produced by your intestinal bacteria.

The stratified squamous epithelial mucosa of the anal canal connects to the skin on the outside of the anus. This mucosa varies considerably from that of the rest of the colon to accommodate the high level of abrasion as feces pass through. The anal canal’s mucous membrane is organized into longitudinal folds, each called an anal column, which house a grid of arteries and veins. Two superficial venous plexuses are found in the anal canal: one within the anal columns and one at the anus. Depressions between the anal columns, each called an anal sinus, secrete mucus that facilitates defecation. The pectinate line (or dentate line) is a horizontal, jagged band that runs circumferentially just below the level of the anal sinuses, and represents the junction between the hindgut and external skin. The mucosa above this line is fairly insensitive, whereas the area below is very sensitive. The resulting difference in pain threshold is due to the fact that the upper region is innervated by visceral sensory fibers, and the lower region is innervated by somatic sensory fibers.

Development

The GI tract begins to develop from the yolk sac in the 4th week. Greater detail is provided here.

Resources and References

OpenStax College, Anatomy and Physiology textbook

Topic Development

authors:

reviewers: