Suturing

last authored: Sept 2009, David LaPierre

Introduction

Suturing is an important component of wound care, repairing moderate to serious injuries such as lacerations, as well as wounds resulting from surgery or other procedures.

Suturing provides effective hemostasis, speeds wound healing, and improves tissue function and appearance. However, it also increases the risk of infection, an important point to remember.

Suturing is a common technique essential for all physicians to know. Simple sutures take little time to learn, but there are extremely challenging wounds and suturing techniques which can take a career to master.

Suture Materials

- types of suture

- size of suture

- types of needle

Types of Suture

Sutures may be described as being natural v.s. synthetic, absorbable v.s. non-absorbable, and monofilament v.s. braided.

An ideal suture would be inexpensive, easy to work with, strong and non-reactive with high knot security. However, no single suture has all these qualities so we have to choose from dozens of options. A number of generalizations may be made about suture materials.

- Virtually all suture materials will be absorbed with time. Non-absorbable sutures are defined as those which retain their tensile strength after 60 days in situ.

- Synthetic sutures tend to cause less reactivity (inflammation) and carry less infection risk than do comparable natural sutures.

- Braided sutures tend to be more reactive and carry higher infection risk than do comparable monofilament sutures.

The majority of accidental wounds in skin will be closed with a monofilament, non-absorbable, synthetic suture such as Polypropylene or Nylon.

type |

strength |

durability |

comments |

resorbable |

|||

monocryl |

|||

vicryl (braided) |

strong |

slowly absorbed |

used for oral lacerations or subcutaneous sutures |

gut |

weak |

rapidly absorbed |

very reactive; rarely used |

nonresorbable |

|||

prolene |

strong |

permanent |

used for skin suturing; slippery |

nylon |

permanent |

used for skin suturing; slippery |

|

silk |

permanent |

used for oral wounds; reactive |

|

stainless steel |

very strong |

permanent |

used for bone; difficult to work with |

Size of Suture

Suture size will be determined by the size of the wound, the amount of tensile strength required in the closure and the need for cosmesis. Larger (thicker) sutures will be chosen for large wounds which are under stress and do not require cosmetic results. Suture size is denoted by a O system with higher numbers indicating sutures of lesser diameter and strength.

Examples of commonly used suture sizes include:

3-0 Closure of fascia, subcutaneous tissue, high stress wounds.

4-0 Closure of low stress wounds i.e. digits, scalp.

5-0/6-0 Cosmetic closure of wounds on the face.

Types of Needle

Once the type of suture is chosen, you must decide on the size of suture and the size and type of needle required. Needles can be divided into two basic types - Cutting and Non-Cutting. There are subcategories of these needles which need not be addressed here. Cutting needles have a triangular cross section and, as their name suggests, cut the tissue they are placed in. They therefore require less force to pass but leave a small puncture wound. Cutting needles are preferred for skin suturing. Non-cutting needles are round in cross-section (Fig 1.).

They push the tissue aside and allow it to close around the suture. More force is required to pass the needle through resistant tissue. They are generally chosen for organ repair or subcutaneous closure.

An example of a typical modern surgical needle is shown below (Figure 3.2). It consists of a tip (technical term = pointy end), body, swaged end and the suture. The majority are curved, although straight needles are occasionally used. Needle sizing and nomenclature is complicated. In general, needle size will be determined, to a large extent, by the size of suture you choose. A good rule of thumb for skin suturing is that the needle should be able to pass all the way through the wound and out the other side, allowing you to grasp it with a forceps or needle driver.

Suture Technique

There are many stitches to master and choose from, according to wound type and condition. Wound edges should be well-approximated, parallel to skin tension lines and with no distortion. The ideal scar is flat and narrow. Slight eversion is much preferred to inversion to improve scarring.

- choosing the stitch

- simple interrupted

- mattress

- subcuticular

- running

- other stitches

Choosing the Stitch

The placement of individual sutures may be determined by a number of factors. For simple, linear wounds, it is often best to mentally divide the wound in half, placing the first suture in the middle. Each half of the remaining wound may then be mentally halved, sutured and so on. This technique avoids the wound edges becoming uneven, resulting in the dreaded ‘dog ear’.

If a wound has specific landmarks such as a jagged point or an identifiable skin crease, it is often best to suture these points first. The result will be a better anatomic alignment of the wound.

Sutured wound edges should have only enough tension to pull them into approximation. If the skin is bulging between the sutures or blanching from pressure, this indicates that the sutures are too tight. They should be replaced in order to avoid skin edge necrosis and scarring.

Eversion of Wound Margins

Sutured wound margins have a natural tendency to roll inwards or invert. This in undesirable because it places two layers of epidermis next to each other. The dermal and subcutaneous tissues are not closely approximated. This results in a deeper and wider scar. Instead, we attempt to evert (roll outwards) the wound edges when we suture skin.

There are a number of ways to achieve wound eversion. When placing simple interrupted sutures, the depth of the stitch should be a little greater than its width. This requires that the needle enter and exit the skin at a 90 degree angle. Vertical or horizontal mattress sutures will also promote wound eversion - frequently, physicians will alternate mattress sutures with simple interrupted sutures to achieve the desired result.

Nov 06, 2007 - Dave's first suture efforts

Simple Interrupted

used with permission, Olek Remesz

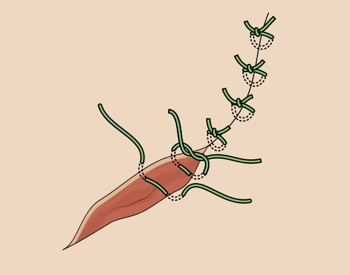

This is the most basic suture technique, in which a series of individual sutures is placed in the skin.

A synthetic, monofilament, non-absorbable suture is usually chosen.

This method is almost always chosen for accidental wounds for several reasons. It provides a secure closure which may be tailored to the individual wound. It allows irregular shaped or jagged wounds to be closed cosmetically.

© 2006-2007. PocketSnips (http://www.pocketsnips.org).

Video - Suturing. Not a substitute for medical advice.

If the wound becomes infected, one or more sutures may be removed to allow drainage, without necessarily opening the entire wound.

It is, however, the most time consuming method.

Horizontal Matress

used with permission, Olek Remesz

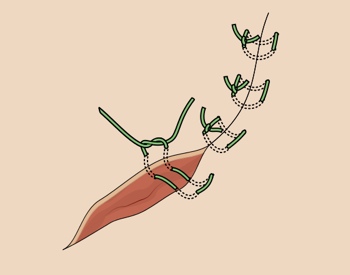

This is a type of interrupted stitch which securely holds the edges of a wound while promoting eversion of the wound edges.

One side of this stitch can be subcuticular (half buried) - this is particularly handy for suturing the edges of a skin flap.

used with permission, Olek Remesz

Vertical Matress

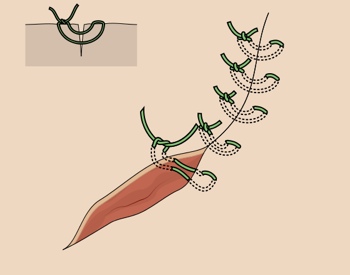

Promotes eversion of the wound edges but may compromise blood flow to the tissue.

It may be used in an alternating fashion with simple interrupted sutures in order to achieve eversion.

Subcuticular

used with permission, Olek Remesz

May be required to close ‘dead space’ (empty space which may allow blood or fluid collection and thus promote infection), approximate subcutaneous structures or reduce skin tension (desirable in that this will reduce the potential for scarring). It is generally performed with a synthetic, absorbable suture. Knots are typically placed at the bottom of the wound where they are less likely to cause scarring.

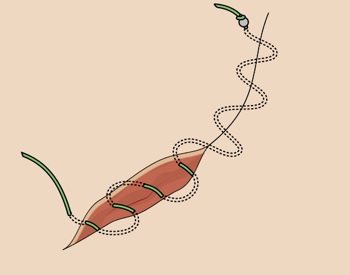

A single length of absorbable suture is wound back and forth through the subcuticular layer of kin and tied at either end. This gives an excellent cosmetic result in straight, clean wounds and is therefore often used for cosmetic surgical closures. This technique is difficult in irregular wounds. An absorbable suture may be used, avoiding the inconvenience and discomfort of suture removal. Some prefer to use a non-absorbable suture which must be pulled out from one end of the wound. The same issues of infection and knot security apply as for a continuous running suture.

Running Stitch

A single length of suture is used to secure the wound and is tied at each end. A non-absorbable, synthetic monofilament is usually chosen. While being one of the fastest methods of wound closure, it is unwieldy for use in irregular shaped wounds.

If the wound becomes infected and requires drainage, the entire closure may be sacrificed. Similarly, if the knot becomes untied, the entire closure is lost.

Other Stitches

Other important stitches used include:

- deep dermal

Types of Wounds

When closing dirty wounds, ensure to wound is thoroughly decontaminated, and consider most appropriate means of closure. Suturing may not always be indicated.

Surgical wounds have many more options regarding closure due to the control in their creation. In fact, surgery is often planned according to closure technique.

Staples are more commonly used in surgical than in accidental wounds. They are unwieldy when compared to interrupted sutures for small or irregular wounds, however, they allow for a rapid closure of linear wounds when cosmesis is not a concern. One or more staples can be removed, if required, for an infection.

Duration of Sutures

Area Face Scalp Neck Upper Extremity Trunk Extensor surface Lower Extremity |

Removal time (days) Suture time can be extended in cases of:

4-5 7 5-8 8-14 7-10 14 14-28 |

Additional Resources

eMedicine - suturing techniques