Advanced Airways

last authored:

last reviewed:

Introduction

Endotracheal intubation, which involves the placement of a flexible tube into the trachea, is one of the highest acuity components of airway management.

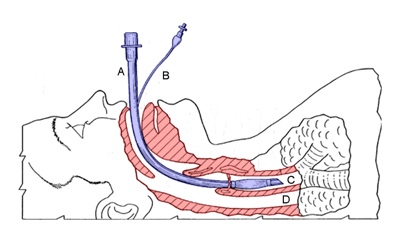

Endotracheal tube in place, used with permission

Tracheal intubation is potentially a very dangerous invasive procedure that requires a great deal of clinical experience to master. When performed improperly (e.g., unrecognized esophageal intubation), the associated complications may rapidly lead to the patient's death.

Despite these concerns, endotracheal intubation is still the gold standard in airway care and provides the highest level of protection when moving a casualty, against vomitus and regurgitation, and from upper airway and maxilofacial haemorrhage.

Indications and Contraindications

- indications

- contraindications

Indications

Entotracheal intubation is used:

- to establish airway in patients in respiratory failure: hypoxia, hypercapnia, tachypnea, apnea, asthma, pulmonary edema, infection, COPD, etc

- to prevent aspiration

- to facilitate suction

- to allow positive pressure ventilation

- to administer drugs during cardiac arrest

- in situations where there will be future need of intubation

- to treat shock

Most opportunities for intubation occur with anesthesia, prior to surgery. This creates a controlled environment.

Contrainications

Contraindications of endotracheal intubation include:

- inability to extend the head: severe arthritis or spinal degeneration

- severe trauma to the cervical spine or anterior neck

- epiglottal infection

- mandibular fracture

- uncontrolled oropharyngeal hemorrhage

Assessment and Predicting Ease of Intubation

LEMON

- Look

- Evaluate

- Mallampati

- Obstruction

- Neck

If not yet done, perform a brief history:

- Allergies

- Medications

- Past Medical History

- Last Meal

- Events

If not yet done, perform a brief physical exam, including vital signs, chest auscultation, and fluid status.

Focus on the airway:

- Mallimpati classification

- neck mobility

- airway anatomy

There are many factors influencing ease of intubation:

- history of craniofacial traumas/previous surgery

- bone or dental malformations

- obstructions (stridorous breath sounds, wheezing, etc)

- neck mobility (can patient tilt head back and then forward to touch chest)

Evaluate using the 3,3,2 rule

- three of the patient's fingers should be able to fit into his/her mouth when open

- three fingers should comfortably fit between the chin and the throat

- two fingers between the floor of the mouth and the thyroid cartilage

Mallampati class: Ask the patient to widely open their mouth. Class IV is associated with more difficult intubations

- class I: total uvula visible

- class II: partial uvula visible

- class III: only top of uvula visible

- class IV: no uvula present

Preparation

Preparation is everything. Have a colleague present to assist. Obtain informed consent if possible. Ensure IV access to provide medications and fluids.

Preparing for advanced airway: SOAP-ME

- suction

- oxygen

- airway equipment

- pharmacology

- monitoring equipment

Select and check all equipment. Check suction, laryngoscope light, inflate balloon and check for leaks, lubricate ETT tip and spray lidocaine on outside and inside.

Ensure monitors are in place for the following:

- blood pressure

- pulse oximetry

- cardiac monitor

- end-tidal CO2, if available

Observe univeral precautions and clean technique.

Pre-oxygenate with 100% oxygen using a facemask. Ensure a pulse oximeter is on.

Positioning

Place patient on back, with head tilted back in the 'sniffing' position if no spinal injury is suspected. Endeavour to have the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal airways all aligned to 180 degrees as much as possible.

Remove dentures. Place a pillow under the head, bringing ear to the level of the sternum. Keep the sternum parallel with the floor.

Medications

Comprehensive information on sedation and paralysis can be found here.

In general, prior to intubation, the patient will need to be rendered unconscious and paralyzed to permit insertion of the airway. The patient may already be unconscious, however, making this step unnecessary. There are a select few cases where patients will be left awake before intubation, but these are rare.

Premedication

|

Sedative/Anaesthetic

|

ParalysisSuccinylcholine if fast-acting but not reversible. It also cannot be used in patients with a history of malignant hyperthermia. It can cause hyperkalemia in rare cases.

Rocuronium has slower onset and is longer-lasting. It can be reversed with neostigmine. |

Before proceeding with paralysis, ensure you are able to ventilate the patient using BVM. However, avoid overzealous positive pressure ventilation, which increases aspiration risk and doesn't appear to increase duration of apnea without desaturation.

Endotracheal Intubation

- Equipment Required

- Placing the Tube

- Confirming Placement

Equipment Required

Endotracheal tube

Endotracheal tubes are available in various sizes, the larger equipped with inflatable cuffing to seal the tube against the tracheal wall. Use as large a tube as possible. A good rule of finger is to choose tube size according to the patient's pinkie diameter.

- neonates and full-term infants: no 0 and 1

- pediatrics: interior diameter = (age in years/4) +4

- adult women: 7-8 mm

- adult men: 8-8.5 mm

Check length. The tube should extend from the mouth to beyond the sternal notch.

Blades

The rigid laryngoscope is designed to lift the tongue and epiglottis, allowing visualization of the vocal cords.

Blades come in different shapes and sizes. The straight Miller blade is useful for children and in situations where the patient has a large epiglottis, as it is designed to lift this structure. Blade sizes are normally 2 or 3 for adults.

The curved MacIntosh blade works best in adults, especially those with obesity. Blade size can be estimated by measuring the length from the patient's lips to the angle of the mandible; blade sizes are normally 3 or 4.

Other Equipment

- gloves, mask, protective eye wear

- oxygen supply and tubing

- bag valve mask apparatus

- selection of oral airways to facilitate BVM

- laryngoscope handle, plus a spare

- rigid suction catheter, Yankauer, 10-12 French

- tracheal suction catheter

- stethoscope

- 10 cc syringe (to inflate cuff)

- flexible intubating stylette

- clock

- pulse oximeter

- cardiac monitor and defibrillator

- CO2 detector

- Magill forceps (to remove foreign material)

- water soluble lubricant

- lidocaine jelly and spray

- 3 ft Twill Tape - for securing ET to patient

- scissors

- rescue devices (eg bougie, LMAs, glidescope, lightwand)

Placing the Tube

Filmed at the Dalhousie Learning Resource Centre.

With the head in the sniffing position, use a chin lift and jaw thrust.

Stand behind the patient's head, and ensure the height is comfortable.

Insert the stylet if you will be using it, ensuring it does not reach the end of the tube.

Begin a 20 second count. It can be helpful for the operator to hold their breath during intubation attempts; if they need to breath, the patient does also, and attempts should be paused as the patient is re-oxygenated.

Remove mask and open the mouth.

Hold the laryngoscope in the left hand and turn it on by flipping down the blade. Open the mouth with the fingers of the right hand. If using a straight (Miller) blade, insert on the right side of the tongue and push the tongue to the left. If using a curved blade, insert in the center of the mouth.

Push the blade posteriorly until the tongue is no longer visible. Use the right hand to protect the lower lip.

Once you are past the tongue, and the teeth and lips are clear, lift the laryngoscope forwards and upwards. A 30-45 degree angle is ideal. Avoid levering backwards, ie using biceps power. Again, avoid contact with both upper and lower teeth.

Visualize the vocal cords. If this is not possible, as an assistant to perform the Sellick maneuver, in which the thumb and index finger are used to provide cricoid pressure. However, cricoid pressure can make ventilation or intubation more difficult. Proper technique is important, using 10-20N of pressure (approx 1 kg). BURP - backwards, upwards, rightwards pressure.

Use suction or McGill forceps to remove secretions or material, as required.

If the patient gags, use topical lidocaine or IV anaestesia or benzodiazepines.

Without taking your eyes off the cords, gently pass the endotracheal tube between vocal cords, advancing the cuff completely through and 2-3 cm beyond the cords. The tube should rest just above the carina, or approx 23 cm from the mouth in men and 21 cm in women. For children, this can be estimated as (age in years/2) +12.

If desired, a malleable stylet may be used to provide form to the ETT. Ensure inside of tube is lubricated to facilitate stylet removal.

Keep holding the ET tube and withdraw the blade. Stabilize against the patient's face. Remove the stylet if you have used it.

Inflate the cuff with 10-20 cc of air. Avoid overfilling, as evidenced by increased resistance, as this can cause tracheal damage.

Ventilate through the tube. Look for signs of correct placement (described in next section).

If unsucessful within 20-30 seconds, remove laryngoscope and re-oxygenate patient before continuing.

Confirming Placement

Do 5 point ausculation first over the epigastrium and then 2x each lung while ventilating. Bubbling sounds over the epigastrium suggests esophageal intubation - deflate cuff and repeat intubation.

If breath sounds are heard more clearly in one lung, mainstem bronchus intubation is likely. Deflate cuff, withdraw ETT by 1-2 cm, and reassess.

A CO2 meter should be applied to the ETT, with colour change observed. Gold is good; yellow is yes.

Once placement is satisfactory, secure tube with twill tape and continue ventilating.

Confirm ETT placement with CXR.

Laryngeal Mask Airways

A laryngeal mask airway (LMA) is a suitable alternative to an endotracheal tube, and has the advantage of requiring a lower level of training that an ET tube.

However, it does not protect the airway, and there presents increased risk of aspiration. Also, higher pressures of ventilation are not possible, given the lack of tight seal that is obtained. This makes it less helpful in obese patients or others with increased chest wall resistance.

The tip of the LMA is advanced to the esophageal sphincter. The cuff is inflated to create a seal above the larynx, rather than in it.

Difficult or Failed Intubations

Difficult airways includes both difficulty with bag-valve-mask ventilation and difficulty with intubation by a skilled operator. Difficult airways contribute to a high risk of morbidity, such as hypoxic brain injury, and mortality.

Difficult mask ventilation predictors

|

Difficult intubation predictors

|

Emergency aiway management can also be made much more challenging by the following:

- secretions, blood, broken teeth, etc

- unfasted state and aspiration

- head and neck trauma

- cervical instability and C -collars

- little time for preparation

- stressful environemnt

There are difficult airway intubation algorithms specific for different institutions. Some examples are seen with the ASA and the AMA (FIND THESE).

If an airway is proving challenging to secure, there are a number of options:

- BURP: backwards, upwards, rightwards pressure

- change the blade

- use a Bougie (below)

- select more experienced personnel to intubate

A failed airway describes a situation where the team cannot intubate and maintain sats above O2 above 90%. In these situations, rescue approaches must rapidly be applied.

Video laryngoscopy uses a device with a fibre-optic camera embedded within the laryngoscope blade. This allows straightforward visualization of the cords for endotracheal tube placement.

Bougie

Other options include:

- jet sufflation

- lighted stylet

- Bullard

- retrograde intubation kit

- Combitube: two cuffs - one in the pharynx and one in the esophagus. Can be placed blindly

- King LT

- bronchoscopy

Possible Complications

Short term complications include:

|

Longer term complications include:

|

Additional Resources

Ptolemy - advanced airway in trauma and critical care

University of Virginia - Dept of Anaesthesia

Penn State - Department of Anesthesia, Difficult Airway Modules