Vibrio cholerae

last authored:

last reviewed:

Introduction

Cholera is a serious gastrointestinal disease caused by the bacteria Vibrio cholerae.

With effective management, using low-cost therapies, mortality rate can easily be less than 1%. However, if care is not adequate, mortality can be much higher, up to 30-50% in patients who suffer from full-blown disease. In Haiti during the 2010 epidemic, mortality was initially 6% (Harris et al, 2010).

The Case of...

Epidemiology

Classification and Characteristics

Vibrio cholerae is a gram-negative bacteria.

The symptoms of cholera are caused primarily by cholera toxin, the main virulence factor of the bacteria. Cholera toxin consists of two subunits - the enzymatic A subunit and a pore-forming penameric B subunit.

A molecular image of the cholera toxin is provided here.

image by David LaPierre

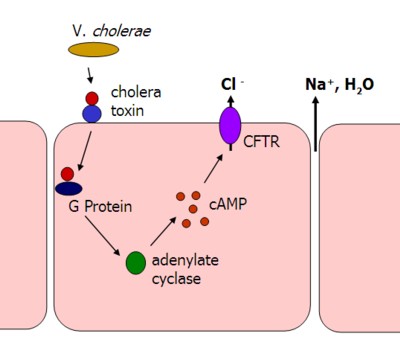

Cholera toxin is released from bacteria in the gut lumen and binds to receptors on enterocytes, triggering endocytosis, or internalization into the cell. Following activation in the cytosol of an infected cell, the A subunit enzymatically activates a G protein and locks it into its GTP-bound form through an ADP-ribosylation reaction. Cholera toxin can then go on to activate other G proteins.

Constitutive G protein activity leads to activation of adenylyl cyclase and increased cAMP levels. High cAMP levels then go on to activate the membrane-bound CFTR protein, leading to dramatic efflux of chloride, sodium, and water from the intestinal epithelium.

Transmission and Infection

Cholera is propogated by fecal-oral spread, usually as a result of poor sanitation and water contamination.

V. cholerae binds to the wall of the small intestine with pili and produces cholera toxin, resulting in massive water and ion loss in the absence of mucosal damage.

The Gobal Health Media Project has produced an excellent patient-focused video on cholera transmission and prevention.

Clinical Manifesations

The incubation peroid of cholera is 1-3 days.

Symptom onset is usually abrupt and severe. Cholera is characterized by:

- large-volume, 'rice-water' diarrhea

- vomiting

- occasional abdominal pain or cramping

Stool loss may exceed 1L/h in adults but is usually much less. Water and electrolyte depletion leads to thirst, muscle cramps, weakness, sunken eyes, and wrinkling of skin on the fingers. Severe metabolic acidosis with K+ depletion, but normal Na+ serum concentration, occurs.

Diagnosis

To reduce mortality to less than 1%, it is critical to effectively assess and triage patients regarding dehydration status.

Treatment

Rehydration

Oral and intravenous rehydration is a mainstay of treatment.

Antibiotics

While antibiotics do not improve mortality if fluids are adequately given, "during an epidemic, antibiotics should be given to all hospitalised patients as soon as possible" (Harris et al, 2010). The rationale is that antibiotics:

- shorten the course of diarrhoeal illness, promoting rapid discharge from hospital

- reduce the volume of diarrhoeal stool output by up to 50%

- reduce the duration of shedding of infectious organisms in the stool from several days to about 1 da

There are many resources available to guide diagnosis and treatment:

- Cholera Outbreak Training and Shigellosis (COTS) Program (also available in Creole)

Resources and References

Harris JB et al. 2010. Cholera's western front. Lancet. 376 (9757):1961 - 1965.

Cholera Outbreak Training and Shigellosis (COTS) program

WHO - First steps for managing an outbreak of acute diarrhoea

WHO. The treatment of diarrhoea: a manual for physicians and other senior health workers.