Treponema pallidum

last authored: Dec 2010, Shannon Tuvey

last reviewed: Oct 2011, Anis Rehman

* caution; graphic photo below

Introduction

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, a bacterial species. Syphilis has been a recognized clinical entity for many centuries, with the first recorded case described in 1494 among soldiers.

Like tuberculosis, syphilis has been nicknamed "The Great Imitator" because the clinical manifestations of late-stage syphilis are protean. While syphilis is a treatable infection, long-standing unrecognized infection can have systemic implications and can even result in death. Maintaining a high index of suspicion, and testing for syphilis where clinically appropriate, can prevent dire long-term consequences.

The Case of John W

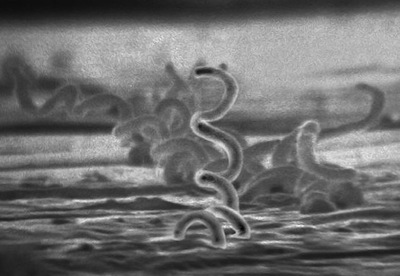

courtesy of CDC (#6803)

A 25 year old male presents with a non-painful, non-puritic penile sore. There has been no penile discharge, and no dysuria. He has not noticed no other rashes and has not experienced fever, chills, weight loss, or malaise. He does not complain of abdominal pain or joint pain. He is bisexual, not in a monogamous relationship, and uses condoms "sometimes". He has never had a sexually transmitted infection in the past, and does not recall getting cold sores. There is no past history of intravenous (IV) drug abuse.

On exam, you find the lesion as shown. You detect several non-tender, discrete, firm, superficial, mobile lymph nodes bilaterally in the inguinal region.

- What is the most likely diagnosis? How will you confirm this?

- If your clinical diagnosis is supported by further investigations, what is your treatment plan?

- What is the natural history of this disease if left untreated?

Epidemiology

Syphilis is distributed worldwide. However, most new cases occur in Central America and the Caribbean, South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. The World Health Organization estimates that there were 12 million new cases of syphilis globally in 1999 (ref).

Up to 1/3 of patients with untreated primary syphilis will develop tertiary syphilis later in life, with significant clinical consequences involving the cardiovascular and neurological systems.

Classification and Characteristics

Treponema pallidum is a thin, tightly coiled spirochete - a minuscule gram-negative bacteria. They are motile with the aid of 6 endoflagella situated between the bacterial membrane and the peptidoglycan layer. Other well-known clinical presentations caused by treponemes include yaws (T. pertenue), pinta (T. carateum), and endemic/nonvenereal syphilis or bejel (T. endemicum). Other spirochete genera include Borrelia (e.g B. burgdorferi or Lyme disease and B. recurrentis or relapsing fever) and Leptospira (e.g. L. interrogans or leptospirosis).

Transmission and Infection

Syphilis is transmitted by individuals in the primary or secondary stages of infection. It enters the body of a new host through microscopic skin or mucous membrane abrasions. Lesions of primary and secondary syphilis, including chancres and condyloma lata, are very infectious and approximately 66% of exposed primary contacts will become infected.

Modes of transmission include

- close personal contact (sexual contact, kissing, or other close contact with mucocutaneous lesions)

- blood transfusions

- ccidental bacterial innoculation

- transplacental passage

Because T. pallidum is very susceptible to environmental insults such as drying, heat, and disinfectants, it has a very low survival rate outside the human body and does not persist on fomites.

Syphilis facilitates HIV transmission. In an HIV-infected individual, syphilis breaches mucosal barriers and thus increases HIV shedding. In an HIV-susceptible individual, syphilis induces a breach in the mucosal barrier and also recruits HIV-susceptible cells to the area of inflammation. Conversely, HIV is thought to alter the natural history of syphilis. In particular, HIV-positive patients may evince atypical clinical manifestations of syphilis and may experience a more rapid course of progression to later stages of the disease including neurosyphilis. However, the degree to which HIV affects the clinical course of syphilis is still hotly debated.

Clinical Manifesations

Because T. pallidum does not produce a known toxin or induce local tissue destruction through enzyme generation, clinical manifestations of syphilis are due to the host inflammatory response which include inflammatory cell infiltrates, neovascularization, and granulomatous changes. Once a new host is infected, the initial incubation period depends on inoculum size. The mean incubation period is 3 weeks, although incubation can last up to 10 weeks.

Syphilis has classically been divided into several stages based on clinical manifestations. Not every patient will evince all stages of the infection. Some patients will enter disease latency after the primary stage, and some will remain clinically disease-free after the secondary stage. The incubating stage represents the period from initial inoculation to chancre development.

Differential diagnosis for genital ulcers would primarily include chancroid, herpes simplex virus, granuloma inguinale, and lymphgranulosum venereum. Because the clinical manifestations of the disease are so diverse and the disease is systemic, the differential for secondary and tertiary syphilis is extremely broad and will not be elaborated here.

Primary stage

The first clinical manifestation of syphilis is typically a painless nodule at the site of inoculation, which ulcerates to become a painless chancre, the hallmark of primary syphilis. The chancre is typically a non-exudative ulcer, 1-2 centimeters in diameter, with a raised and indurated edge. The underlying mechanism is treponemal proliferation at the site of inoculation, with an associated host immune response. Associated signs of the primary stage include bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy due to treponemal proliferation in regional lymph nodes. Occasionally, multiple primary chancres may appear in an immunocompromised patient, such as one co-infected with HIV. In the absence of any treatment, the chancre will generally heal spontaneously in 2-8 weeks. Approximately 75% of individuals with primary syphilis will proceed to latent infection. The other 25% will go on to develop secondary syphilis.

Secondary stage

Secondary syphilis, courtesy of CDC (#4143)

The secondary stage, consisting of rash and mucocutaneous lesions, can begin 2-12 weeks after initial infection, but the mean latency is 6 weeks. The rash is generalized, maculopapular, and polymorphic. Involvement of the palms and soles is classic, and not typical of most generalized rashes. In the secondary stage, condyloma lata occur. These are hypertrophic papular lesions which are usually concentrated in moist areas near the vulva and anus and resemble condyloma acuminata lesions (genital warts) due to HPV infection. Constitutional signs and symptoms may also be prominent during the secondary stage, including generalized lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, fever, malaise, and arthralgias. After the secondary stage, most patients enter a latent stage in which the disease is asymptomatic but serologic tests remain positive. The latent stage is variable in duration and patients may relapse once or several times and re-enter the secondary stage. Relapses are possible up to 4 years after initial infection, but 75% of relapses will occur within the first year. To differentiate patients based on likelihood of relapse, the latent stage is dichotomized between early (less than 1 year) and late (greater than 1 year). Up to one third of untreated patients with primary syphilis will develop late, or tertiary syphilis. The latency period between secondary and tertiary syphilis is highly variable and can range from 3 to 30 years.

Tertiary stage

Tertiary syphilis is characterized by diffuse chronic inflammation. Tertiary syphilis is characterized by diffuse chronic inflammation and the clinical manifestations include arterial lesions (aorta and Central Nervous System) and gummas of the skin, bones, liver, CNS (Central Nervous System), and spleen.

Congenital syphilis

Maternal syphilis infection may lead to intrauterine infection and congenital anomalies, with transplacental transmission rates approaching 100%. More than 40 % of pregnancies affected by intrauterine syphilis will result in intrauterine fetal demise. The incidence of premature delivery, with its attendant risks for the neonate, is also increased in congenital syphilis. The manifestations of congenital syphilis can be divided into early and late based on the patient age. The early stage of congenital syphilis occurs within 2 years of birth and is due to disseminated treponemia, analogous to the secondary stage of sexually-acquired syphilis. Signs and symptoms may include poor feeding, "snuffles" (syphilitic rhinitis), hepatosplenomegaly, mucocutaneous lesions, and osteochondritis. The late stage of congenital syphilis is due to chronic inflammation and scarring, and occurs in patients at least 2 years old. Classically, congenital syphilis is characterized by Hutchinson's triad of interstitial keratitis, eight cranial nerve deafness, and Hutchinson teeth. However, other manifestations of late congenital syphilis may be evinced, including saber shins, frontal bossing, mulberry molars, saddle nose, rhagades, and Clutton joints. It should be emphasized that timely diagnosis and treatment can halt the progression of this disease, since the clinical effects are due to ongoing infection rather than to intrauterine disease.

Diagnosis

Syphilis is most commonly diagnosed by serological testing. Non-treponemal antibody tests should be distinguished from specific antibody tests.

Non-treponemal antibody tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and Venereal Diseases Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests, are commonly used for screening asymptomatic individuals. The RPR test is more sensitive than the VDRL test, without any compensatory reduction in specificity. Both tests have a high false-positive rate and conditions such as pregnancy, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and malaria can result in false-positive screening test results. Any positive RPR or VDRL test should be confirmed with a specific antibody test before commencing treatment; neither test is capable of differentiating between different treponemal species. VDRL titres can be utilized to follow the clinical response to treatment.

Specific antibody tests include the Treponema pallidum Hemagluttination (TPHA), Microhemagluttination (MHA-TP), and Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody Absorption (FTA-ABS). Of these tests, the FTA-ABS is the most sensitive and therefore the most frequently employed. In contrast to the non-treponemal antibody tests, the FTA-ABS will remain positive for the lifetime of almost all infected individuals, even after treatment and subsequent resolution of the infection.

If serological testing is not available, immunofluorescence, use of the Warthin-Starry silver stain, and dark-field microscopic examination of preparations from chancres or moist lesion are alternative methods of identifying that a spirochete is present, but microscopy does not permit separation of treponemal species based on morphological characteristics. These organisms are too small to be visualized using light microscopy. The pathological treponemal species have never been successfully cultured in the laboratory.

Patients with tertiary syphilis should be screened for aortic dilatation with a chest radiograph. If neurosyphilis is suspected, due to symptoms or with a titre that does not not decrease with treatment, lumbar puncture may be performed. The CSF should be sent for VDRL testing, cell count, and quantification of protein level.

All patients diagnosed with syphilis should be offered HIV testing. Conversely, routine testing for syphilis should be performed regularly (up to several times annually) in high-risk HIV-positive individuals. It is worth noting that serology can be unreliable in HIV-positive individuals, who are more likely to yield false-negative results. If the clinical presentation is highly suggestive of syphilis despite negative serology, further testing such as tissue biopsy or dark-field microscopy may be indicated.

Treatment

Treatment is guided by duration of infection.

If patients have been infected within one year, treatment should be one dose of penicillin.

If patients have been infected for greater than one year, or if late syphilis is present, treatment should be three doses, each given one week apart, of penicillin.

If neurosyphilis is present, aqueous penicillin G should be given.

Contacts should be treated with penicillin.

If a patient is allergic to drugs, doxycycline, tetracyclin, erythromycin, or ceftriaxone may be considered for primary or secondary syphilis. Patients with neurosyphilis, or syphilis in pregnancy, should be treated with penicillin desensitization (Birnaum et al, 1999).

Resources and References

American Academy of Pediatrics. Syphilis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, McMillan JA, eds. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006: 631-644.

Birnaum NR, Goldschmidt RH, and Buffett WO. 1999. Resolving the Common Clinical Dilemmas of Syphilis. American Family Physician.

Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, Riesenberg K. 2009. Syphilis and HIV Co-infection. European Journal of Internal Medicine 20(1):9-13.

Liu PF, Euerle B, Chandrasekar PH. Syphilis [eBook]. eMedicine Infectious Diseases. 2010 Sept 22 [cited 2010 Dec 1].

Lynn WA, Lightman S. 2004. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous combination. Lancet Infectious Diseases 4(7):456-66.

Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

Mims C, Wakelin D, Playfair J, Williams R, Roitt I. Medical Microbiology. 2nd ed. London, UK: Mosby International Ltd; 1999.

Pialoux G, Vimont S, Moulignier A, Buteux M, Abraham B, and Bonnard P. 2008. Effect of HIV Infection on the Course of Syphilis. Aids Reviews 10(2):85-92.