Supraventricular Tachycardias

last authored:

last reviewed:

NOTE: INCOMPLETE - authoring underway!

Introduction

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) describes a rhythm, either physiologic or pathologic, that originates above the bundle of His - that is, within the atria or the AV node.

Sinus tachycardia can occur normally due to changes in the body outside the heart, during exercise or stress, after administration of various drugs, or following a host of pathological processes. It normally resolves following removal of the precipitating cause.

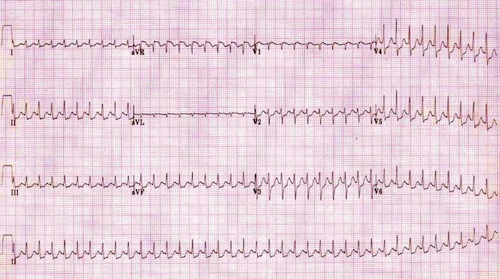

AV nodal re-entry tachycardia at 220bpm, courtesy of Life in the Fast Lane

Tachydysrhythmias may also result directly from abnormal heart function, mediated by aberrant electrical activity in the atria, ventricles, or the electrical conducting system. They may spontaneously resolve, or they may persist if not addressed.

In a few cases, they may also lead to an increasingly chaotic rhythm of the heart and result in pulseless ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation, with imminent death if immediate treatment is not offered.

SVTs may be considered regular or irregular. They are commonly narrow complex, though not always so; a bundle branch block, aberrant conduction, or accessory pathway may lead to a wider QRS complex.

Regular Forms of SVT include:

sinus tachycardia: physiologic response to a variety of factors

AV Nodal re-entry tachycardia (AVNRT): common, normally benign and self-limited

atrioventricular re-entry tachycardias (AVRT): less common; may be dangerous

atrial tachycardia: ectopic focus within the atria

atrial flutter: see main topic here

automatic junctional tachycardia: rare

Irregular Forms of SVT include:

atrial fibrillation: common rate abnormality; see main topic here

multifocal atrial tachycardia: mutiple sites of atrial irritability and impulse generation; may develop into atrial fibrillation

atrial flutter with variable block:

Pathophysiology of SVTs

main article: electrical control of the heart

There are many underlying processes that can lead to tachycardias:

Ectopic Rhythms: If an area of tissue develops an intrinsic rate of firing faster than that of the SA node, ectopic (premature) beats can occur. They can occur due to high catecholamine concentrations, hypoxemia, ischemia, electrolyte disturbances, and drugs such as digitalis.

Abnormal Automaticity: Injured cardiomyocytes can acquire automaticity and spontaneously depolarize, though means not fully understood, but likely involving a slow calcium current.

Triggered Activity: Under certain conditions, action potentials can trigger abnormal depolarizations that result in extra heart beats or rapid arrhythmias. Afterdepolarizations appear as oscillations and can be early, during repolarization, or delayed. Early afterdepoloarizations are most common during conditions that prolong APs, such as long GT syndrome.

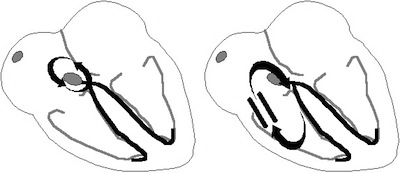

Re-entry Pathways: AV nodal re-entry on the left; accessory pathway

re-entry on the right. Courtesy of Life In the Fast Lane

Reentry: Reentry occurs when impulses circuluate around a unidirectional conduction block, recurrently depolarizing a region of cardiac tissue. Reentry around distinct anatomic pathways usually appears as monomorphic tachycardia on an ECG, while fibrillation is likely caused by multiple circulation reentry wave fronts.

Sinus Tachycardia

- overview

- causes

- features

Overview

Sinus tachycardia is a physiologic response, with increased sympathetic tone, following a variety of conditions.

Causes

There are many causes of sinus tachycardia:

Physiologic states

|

Metabolic or pathologic states

|

Medications

|

Features

ECG findings include:

- a heart rate above 100 in adults, or above the normal range for children

- normal P waves and QRS complexes

- the P wave may be hidden in the T wave from the previous beat

AV Nodal Re-entry Tachycardia

- overview

- causes

- features

- pathophysiology

Overview

AV Nodal Re-entry Tachycardia (AVNRT) is a common cause of paroxysmal tachycardia. In contrast to AVRT (below), re-entry is through the AV node.

Causes

AVNRT is normally paroxysmal - occurring in healthy hearts without known cause. It is more common in women.

It may be precipitated by:

- exercise

- caffeine

- alcohol

- salbutamol

- amphetamines

Features

Heart rate is normally between 140-280, and is regular.

The QRS is normally narrow, < 120 ms. It may be wide if a bundle branch block is present, if there is aberrant conduction, or if there is an accessory pathway.

If the P wave is visible, it is normally inverted, due to retrograde conduction through the atria. However, the P wave may be buried within, after, or before the QRS complex.

The ST segment may be depressed if there is sufficient cardiac demand to cause ischemia.

It may terminate on its own, or may persist without intervention.

Pathophysiology

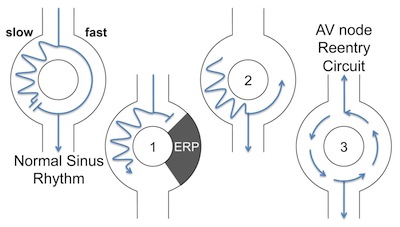

In AVNRT, there is a re-entry loop involving the AV node. Two pathways exist. A slow pathway is slowly conducting, but with a short effective refractory period (ERP). A fast pathway is rapidly conducting, but with a long refractory period.

Re-entry circuit, slow-fast AVNRT, courtesy of Life in the Fast Lane

Slow-fast AVNRT (80-90% of cases): anterograde conduction occurs down the slow AV pathway, and retrograde conduction occurs up the fast pathway.

With depolarization through the atria, signals are sent down both slow and fast pathways. Normally, during sinus rhythm, the fast impulse begins to travel up the slow pathway in a retrograde manner. The impulses, when they meet each other, cancel each other out.

If a second signal from the atria (a premature contraction, for example) occurs immediately after the first, the fast pathway will still be refractory. As a result, it will only travel down the slow pathway. This impulse will travel in a retrograde fashion up the fast pathway, establishing a rapid cycle within the AV node. With each cycle, impulses will pass into the ventricles and back to the atria, causing a rapid heart rate.

Fast-slow AVNRT (10% of cases): anterograde conduction occurs down the fast pathway, while retrograde conduction occurs up the slow pathway. Inverted P waves commonly occur after the QRS, given the slow rate of retrograde conduction.

Slow-slow AVNRT (1-5% of cases), anterograde conduction occurs down the slow pathway, while retrograde conduction occurs up the atria.

Atrioventricular Re-Entry Tachycardias

- overview

- causes

- features

- pathophysiology

Overview

Atrioventricular re-entry tachycardias describe tachycardias that result from re-entry into the atria through accessory pathways. One of the most important of the AVRTs is termed Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, in which an accessory pathway results in pre-excitation of the ventricles from the atria.

Pre-excitation may be present during a normal heart rate; however, with tachycardia, the accessory pathway may act as a re-entry circuit.

Orthodromic conduction occurs down the AV node, and in a retrograde fashion through the accessory pathway.

Antidromic conduction occurs through the accessory pathway, and in a retrograde fashion through the AV node.

Causes

Pre-excitation may be increased with:

- increased vagal tone (eg Valsava maneuvers)

- AV blockade

Features

The heart rate may be as high as 200-300 during periods of AVRT.

P waves may be buried in the QRS complex, or may be retrograde.

The QRS complex is normally <120ms, unless there is:

- antidromic conduction

- bundle branch block

- aberrant conduction

In WPW, the PR interval is <120 ms.

The QRS is prolonged and a Delta wave is evident, resulting from a slurring of the initial portion of the QRS due to re-excitation.

ST segment and T waves are discordant

T wave inversion is common (WHY??)

Pathyphysiology

Atrial Tachycardia

NOTE: this combines AT and MAT; ok to do this?

- overview

- causes

- features

- pathophysiology

Overview

Atrial tachycardia is normally due to a single ectopic area within the atria, in which the case will be regular. More rarely, the beats may originate from a number of areas, causing multifocal atrial tachycardia.

Causes

Atrial tachycardia may be idiopathic, though may also be caused by:

- atrial scarring

- coronary artery disease

- valvular heart disease

- cardiomyopathies

- cor pulmonale

- COPD (especially multifocal atrial tachycardia)

- congenital abnormalities

- increased sympathetic tone

- digoxin toxicity

- hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia

Features

ECG normally shows:

- rate >100 bpm; normally > 120 bpm

- abnormal P wave morphology

- identical P waves in atrial tachycardia; varying P wave morphology in multifocal atrial tachycardia

- narrow QRS, unless BBB, accessory pathway, or aberrant conduction

- isoelectric baseline (??)

Pathophysiology

Atrial tachycardia can occur through increased automaticity, re-entry, or troggered activity.

Multiple atrial tachycardia normally is seen in quite ill patients, and may lead to atrial fibrillation or flutter. The right atrial stretch (Cor pulmonale), along with hypoxia, sympathetic tone and medications, and electrolyte abnormalities, lead to an irritable atria.

Assessing SVT

A tachycardia may represent an unstable, life-threatening condition. Immediately assess and ensure the patient's ABC's (airway, breathing, and circulation) are being managed, as described below.

- history and physical exam

- investigations

History and Physical Exam

Stable vs unstable: Rapidly assess the patient's stability. Obtain a full set of vitals as you talk to, and observe, the patient. Evidence of instability include:

- altered level of consciousness

- chest pain

- significant shortness of breath

- signs of heart failure, especially bilateral crackles in the lungs

If the patient is unstable, rapidly proceed to management with cardioversion, as described below.

History: If the patient appears stable, you may take more time to inquire into the following:

- when did it begin?

- has this ever happened before? Get details, including duration, diagnosis, and treatment, if known.

- have they passed out?

- is there fever, chills, or other evidence of infection?

A review of systems is also warranted.

Past medical history should specifically include questions regarding heart disease and thyroid disease.

Social history should include:

- sleep patterns

- alcohol use

- drug use

- cigarette smoking

- caffeine intake

- stress levels

Physical Exam: Examine the patient's overall state, including: level of consciousness and colour.

Specific attention should be paid to the cardiovascular and respiratory exams.

Investigations

Once a signficant tachycardia is noted, an immediate ECG should be obtained. The ECG will provide an abundance of information on the specific rhythm.

External resources with ECG libraries include:

If investigations are warranted, bloodwork may include:

- CBC

- electrolytes

- creatinine

- troponin

- TSH

- calcium, magnesium

Other tests to investgate a tachycardia can include:

- chest X-ray (investigate for heart failure)

- echocardiogram

Management

Treatment of tachyarrhythmias is meant to stabilize the patient, protect against lethal consequences, and mitigate the underlying cause(s) of the arrhythmia.

Immediate Management of the Unstable Patient

If unstable, the patient should be offered immediate electrical cardioversion. Obtain consent and provide analgesia/sedation as appropriate, but do not delay if the patient is showing rapid signs of deterioration.

It is paramount to assess and address the ABC's when managing a patient with unstable tachycardia. This can include:

- Opening the airway

- Providing supplemental oxygen, postive pressure ventilation, and/or intubation

- IV access x2 and fluid administration

- Ensure monitor/defibrillator in place

Management of stable SVT

Sinus tachycardia is normally treated by addressing the underlying cause, listed above.

For stable tachydysrrhythmias, attempt vagal maneuvers, including carotid massage or the valsava maneuver.

If unsuccessful, adenosine is commonly the initial medication attempted for treatment of SVT in the emergency department, given by rapid IV push.

Other medications to consider given PO or IV (depending on the urgency of the situation), include:

- calcium channel blockers

- beta blockers

- digoxin

- amiodarone

Elective cardioversion may also be offered if control with medications fail.

Longer term management

Once the immediate concerns have been addressed, referral to internal medicine or cardiology is warranted for ongoing management.

Antiarrhythmics must be used with caution due to the high risk of further arrhythmic complications and death.

Catheter ablation can be used to destroy distinct rentry foci, mapped using electrophysiologic techniques.

Implantable cardioverters can be used to automatically cardiovert or defibrillate a heart.

Resources and References

Life In the Fast Lane - SVT ECG library

Topic Development

authors:

reviewers: