Stroke

last authored: April 2010, David LaPierre

last reviewed:

Introduction

Stroke is a rapidly developing group of clinical signs of focal or gobal disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin. With over 5.5 million deaths yearly, stroke is the second-most common cause of death worldwide, accounting for 9% of mortality (World Health Organization, 2000; Murray and Lopez, 1997). It has a staggering impact on society, and as 40% of stroke survivors are left with some degree of functional impairment, stroke is projected to be the fourth-most important cause of disability in 2030 (Lopez et al, 2006). Perhaps 500 people per 100,000 are living with the effects of stroke, and as care continues to improve survival, demands on health care and social-care systems will likely also continue to increase (Donnan et al, 2008).

In Canada, there are 50,000 new patients per year - one every ten minutes. This results in 15,000 stroke deaths/year, and has given Canada 350,000 stroke survivors, at a cost of over $3 billion (Lindsay et al, 2005). Return to work usually not possible; 50% of survivors are dependent and 20% require institutionalization.

75% ofter the age of 65.

For every symptomatic stroke, there are 9 'silent' strokes leaving people with some level of cognitive impairment. There are also transient ischemic attacks, which are diagnosed if the symptoms last less than 24 hours, though usually they last 2-15 minutes. A fuller definition: a brief episode of neuro dysfunction caused by focal brain or retinal ischemia, with clinical symptoms typically lasting less than one hour, and without any evidence of acute infarction.

The Case of...

a simple case introducing clincial presentation and calling for a differential diagnosis. To get students thinking.

Causes and Risk Factors

There are strong differences in age-standardized death rates of stroke around the world - for Russia, death rates for people age 30-69 is 180 per 100,000, while in Canada, the same meausre is 15 per 100,000 (Strong, Mathers, and Bonita, 2007). These differences suggest not only a difference in management, but also prevalence of risk factors and genetic causes. The continued reduction in death rates in the developed world is most plausibly related to increased living standards, reduced cigarette smoking, and improved blood pressure control, suggesting the importance of the same for people around the world (Donnan et al, 2008).

From 15-30% of strokes preceded by TIA, especially those positive on diffusion-weighted MRI scan. The time window for optimal intervention to prevent stroke after TIA is very short.

- ischemic stroke

- hemorrhagic

- stroke risk factors

Ischemic Stroke (80%)

Thrombotic/intrinsic vessel disease originates in the brain's vasculature. Causes include:

- atherosclerosis

- small vessel disease

- vasculitis

- vasospasm

- arterial dissection

- compression

- fibromuscular

- hypercoagulable state (oral contracepives, HRT)

- cerebral venous thrombosis

Embolic disease originates at remote sites. Causes include:

- cardiac wall thrombi (common): myocardial infarct, valvular disease, and atrial fibrillation important predisposing factors

- arterial thromboemboli, particulary from atherosclerotic plaques within the carotid arteries

- septic material

- air

- fat

- tumour

- paradoxical

Lacunar strokes (LACS) are usually due to intracerebral small vessel disease. They are clinically recognizable, with pure motor hemiplegia, pure sensory stroke, or ataxic hemiparesis. They also have the best functional outcomes of all stroke types.

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Intracerebral hemorrhage is responsible for 15% of stroke. Causes and risk factors include:

- hypertension

- trauma

- bleeding conditions (hereitary/acquired thrombophilia)

- amyloid angiopathy

- illicit drug use (ie cocaine)

- vascular malformation

- vasculitis

- hemorrhagic transformation of an infarct or tumour

- rupture of a mycotic aneurysm

- medications: anticoagulants, thrombolytics

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is responsible for 5% of stroke. Younger age of onset is common, with women >men. Causes and risk factors include:

- aneurysm rupture

- vascular malformation

- bleeding conditions (hereitary/acquired thrombophilia)

- trauma

- amyloid angiopathy

- illicit drug use (cocaine)

Risk factors for all types of stroke include:

- hypertension (60% of the population attributable risk)

- lowering 2 mmHg reduces risk by 10

- smoking (2x risk of infarction; 3x risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage)

- diabetes

- hyperlipidemia

- low exercise

- low cholesterol appears associated with increased intracerebral hemorrhage

- heavy drinking (increases risk 2.5x)

- obesity

- oral contraceptives or post-menopausal hormone treatment

Risk factors explain perhaps 60% of attributable risk for stroke, leaving the other 40% currently unaccounted for. A proportion of these may be genetic.

Pathophysiology

As described, stroke can occur following two separate processes: ischemia or hemorrhage.

- Ischemic Stroke

- Hemorrhagic Stroke

Global cerebral ischemia occurs when there is a generalized drop in perfusion such as can occur in cardiac arrest, shock, or severe hypotension. Focal cerebral ischemia follows reduction in blood flow to a given area due to large vessel disease, such as thrombosis or embolus, or due to small vessel disease such as vasculitis.

Global cerebral ischemia occurs when there is a generalized drop in perfusion such as can occur in cardiac arrest, shock, or severe hypotension. Focal cerebral ischemia follows reduction in blood flow to a given area due to large vessel disease, such as thrombosis or embolus, or due to small vessel disease such as vasculitis.

CNS cells show a hierarchy of susceptibility to ischemia, with neurons being the most sensitive. Glial cells are also vulnerable. Differences in blood flow and metabolic needs results in selective vulnerability of different populations following global events.

Thrombotic Stroke

The distinction between TIAs and stroke is arbitrary, as permanent tissue damage can be shown on MRI in at least 25% of patients with TIAs (Kidwell et al, 1999).

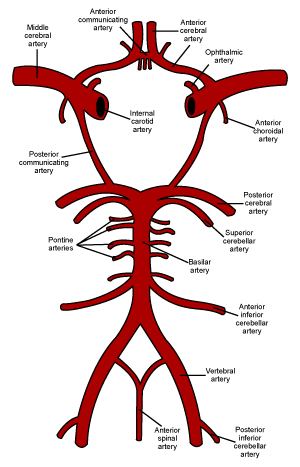

Large vessel stroke is most commonly due to atherothrombosis. These can be found at the bifurcation or siphon portion of the common carotid artery, middle cerebral artery stem, intracranial vertebral arteries, or origin of vertebral arteries.

Small vessel stroke, aka lacunar stroke, is most commonly due to lipohyalinotic occlusion following hypertension or occasionally atheroma. They occur in the penetrating branches of the anterior, middle, or posterior cerebral/basilar arteries.

Cardioaortic Embolic Stroke

Cardiac sources include atrial fibrillation, LV/LA thrombus, rheumatic valve disease, artificial valves, bacterial endocarditis, or atrial myxoma.

Ischemic penumbra

The ischemic penumbra is the structurally intact, but functionally impaired, tissue surrounding the area of infarct. It is the target of intervention, as its restoration can aid recovery. Molecular events begin with energy depletion, disruption of ion homeostasis, release of glutamate, calcium channel dysfunction, release of free radicals, membrane disruption, inflammatory changes, and apoptosis and necrosis (Dirnagl, Iadecola, and Moskowitz, 1999).

Hemorrhagic Stroke

The most common mechanism for hemorrhage is small-vessel disease causing lipohyalinotic aneurysms that rupture. About 2/3 of patients with primary cerebral hemorrhage have hypertension (Thrift, Donnan, and McNeil, 1995). Other causes include arteriovenous malformations, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, or infarction with secondary hemorrhage.

Most subarachnoid hemorrhage is caused by rupture of saccular aneurysms within the subarachnoid space

Signs and Symptoms

The public should be very aware of the signs and symptoms of stroke, as easrly diagnosis is critical. Most patients present late, beyond the tPA window. This can be due to a lack of knowledge, or due to waking up.

Calling 911 is the best approach, as it saves time and can

There are four important questions to answer immediately:

- is the patient stable?

- is this a stroke?

- when did it occur?

- where is the stroke?

- what type of stroke is it? Embolic strokes respect vascular territories

- what is the cause?

Localization can suggest options for therapy and predicts impairments/disabilities.

Cincinnate prehospital stroke scale and LA prehospital stroke screen are available for EMS.

In hospital assessment scales: NIHSS: 15 item scale

- history

- physical exam

History

Assess, as specifically as possible, time of onset of s

Common signs of stroke include:

- weakness

- trouble speaking

- vision problems

- dizziness

- headache

It is important to discover how the patient was beforehand, to tease out causes.

What else is wrong? Assess the patient's prior level of function.

SAH often presents with the "worst headache ever", neck stiffness, nausea, and vomiting. However, mild SAH is frequently misdiagnosed.

Physical Exam

Vital (ABC's) are critical

Localization of the lesion, with attending signs and symptoms,

Neurological exam

- pay attention to visual and

pure motor hemiplegia, pure sensory stroke, ataxic hemiparesis

Investigations

- lab investigations

- diagnostic imaging

Lab Investigations

CBC, lytes, ur, sCr

- blood glucose: Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia are the most common stroke mimics

Diagnostic Imaging

ECG to rule out arrhythmia or acute coronary syndromes.

Immediate imaging is necessary to rule in or out a hemorrhage.

- subdura

While unenhanced CT has been the primary imaging modality for years, MRI is likely the better of the two.

The ischemic penumbra is visible in some patients up to 24 hour after stroke by MRI. Perfusion-weighted imaging can be used to show areas of ischemia and can be compared with the ischemic core, visible by diffusion-weighted imaging.

left MCA infarct causing expressive aphasia

Carotid doppler shows flow velocity and areas of turbulence. A 50% stenosis will give a flow of 130 cm/s, while a 75% stenosis correlates with 230 cm/s.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

With stroke mimics, neurological deficits/symptoms tend to be global rather than focal. Mimics include DIIMMSS:

Young people

- migraine

- multiple sclerosis

- conversion disorders

older patients

- subdural hematoma

- epidural hematoma

- tumour

any age

- hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia

- hyponatremia

- seizure/post-ictal causes (can have focal causes)

- herpes encephalitis

- drug intoxication

- metabolic: hypoglycemia, renal failure, hepatic failure

- syncope

- structural: (tumours, trauma, subdural hematoma)

Prevention

Recommendations Aspirin is not recommended for the prevention of a first stroke in men (Class III, Level of Evidence A). Previous guideline statements have recommended the use of aspirin for cardiovascular (including but not specific to stroke) prophylaxis among persons whose risk is sufficiently high for the benefits to outweigh the risks associated with treatment (a 10-year risk of cardiovascular events of 6% to 10%), and this panel agrees (Class I, Level of Evidence A). Aspirin can be useful for prevention of a first stroke among women whose risk is sufficiently high for the benefits to outweigh the risks associated with treatment (Class IIa, Level of Evidence B). The use of aspirin for other specific situations (eg, atrial fibrillation, carotid artery stenosis) is discussed in the relevant sections of this statement. (Goldstein et al, 2006).

Treatments

The Canadian Stroke Strategy suggests best practices for the following:

- health promotion/primary prevention

- pre-hospital and emergency care

- acute care and treatment

- rehabilitation

- secondary stroke prevention

- community re-engagement/reintegration

- Health Promotion &

Primary Prevention - Pre-Hosptial &

Emergency Care - Inpatient Stroke Care &

Early Rehabilitation - Long-Term

Rehabilitation

- Secondary

Prevention

Health Promotion and Primary Prevention

Hypertension control is top priority in preventing stroke. Lifestyle modifcation is accordingly very important: quit smoking, eat healthy, exercise, and reduce stress.

Small amounts of alcohol decreases risk.

Medication prevention includes lipid-lowering agents, anti-platelet therapy (81 mg ASA), and antithrombotic therapy (warfarin) for atrial fibrillation. However, warfarin is used in only 54% of patients with AF in Canada due to confusion about benefit and perceived risk of complication (Kapral et al, 2005).

For patients with atrial fibrillation unable or unwilling to take warfarin, both aspirin and clopidogrel appear helpful (ACTIVE investigators, 2009).

Pre-Hospital and Emergency Care

Stroke is a medical emergency that requires urgent hospital admission.

Do CT within 45 minutes to rule out hemorrhage and begin fibrinolytics if appropriate (heparin, warfarin, aspirin, tPA). tPA must be used within three hours.

Thrombolysis

Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is one of the most biologically effective treatments for acute ischemic stroke. 2008 Guidelines require treatment within 4.5 hours of stroke onset (Wardlaw et al, 2009), though

This short time window means that only 6/1000 patients benefit with treatment (Gilligan et al, 2005). tPA is effective at improving function, but not at reducing mortality (Hacke et al, 2004) hypertension, very severe neurological deficits, severe hyperglycemia, and possibly with early CT ischemic changes.

The major adverse effect is intracerebral hemorrhage, seen in 6-7% of cases. Increased risk is seen in with increased age.

Give bolus and then drip. Stop if: neurological deterioration, severe headache.

Inclusion criteria:

- acute ischemic stroke in agen >18

- 1h <stroke duration <4.5 hrs

- deficit that is disabling, or measurable on the NIHSS

- no ICH on CT or MRI

- informed consent (usually family)

Exclusion critiera:

- time of onset >4.5 hrs

- ICH on CT or MRI

- symptoms suggestive of SAH

- CT or MRI signs of acute hemispheric infarction involving over 1/3 MCA territory

- history of ICH

- stoke, serious head injury, or spinal trauma within prev 3 months

- seizure at onset

- recent major surgery

- SBP > 185 or CPB > 110mmHg

- elevated INR or PTT

- plt <100 x 109/L

- hypo, hyperglycemia

- any other condition which could increase risk of hemorrhage

Do not give ASA, clopidogrel, or heparin for 24 hours.

Blood Pressure Management

Labetalol 10-20 mg IV over 1-2 minutes

repeat q10 to a total dose of 300 mg

Other options: nicardapine

ICH: neurosurgery should always be consulted.

Largely supportive

Correct coagulopathy if present

Establish goals of care

Acute Stroke Care and Early Rehabilitation

Initial stroke recovery involves resolution of cerebral edema, ionic fluxes, and inflammatory processes.

There is conclusive evidence that organized inpatient care, such as is received on an interdisciplinary stroke care unit (SCU), decreases morbidity and mortality (Phillips, Eskes, and Gubitz, 2002). A core set of performance indicators exists and

Management of patients within a SCU reduces mortality and improves function by about 20% (Langhorne et al, 1993).

Stroke units bring together staff and patients into a single ward, usually at little additional cost. Immediate entry into a stroke unit helps prevent or reduce complications, such as aspiration or dehydration. Benefits depend on coordinated care of a multidisciplinary team, with integration of nursing, staff expertise, close involvement of caregivers, and education for staff, patients, and caregivers. Improved blood pressure control, early mobilization, and general adherence to best practice are all also important (Langhorne and Pollock, 2002; Cadilhac et al, 2004).

It appears SCU management has the potential to prevent death or disability for about 50 patients for every 1000 strokes, compared with 6 per 1000 for tPA and four per 1000 for aspirin (Gilligan et al, 2005).

The acute stroke team plays a substantial role in survival and recovery. An interdisciplinary team should come up with care plan within 48 hours and then begin its implementation. Members of the team include: food and nutrition services, neurology, neuropsychology, nursing, occupational therapy, pharmacy, physiotherapy, rehabilitation medicine, social work, speech-language pathology, spiritual care, team coordinator.

Physiotherapy is highly valued by patients and is effective (Pollock et al, 2007). The strongest evidence supports task-oriented exercise training aimed at improving balance and gait (Van Peppen et al, 2004). The intensity of therapy is important, with increases in time spent showing small but significant improvements. However, what appears to be more effective is the organization and coordination of care delivery by all health care providers involved.

Language impairments are common, an speach and language terapy is common, but understudied.

Cognitive impairment, especially memory deficits, spatial neglect, attention deficits, and mood disturbance are common and should be assessed.

Early rehabilitation, occurring within the first few months following stroke, uses neuroplasticity to recruit and reorganize neighbouring neural networks. At the same time, adaptation and coping strategies are used, based on educational and psychological practice.

Aneurysms can be clipped or coiled.

subarachnoid hemorrhage - prevent re-bleeding; nimodipine to decrease secondary vasospasm.

Acute Blood Pressure Management

Blood pressure control is critical post-stroke, and target blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg. Randomized controlled trials have not been defined, but the best combination appears to be a diuretic and and ACE inhibitor.

Long-Term Rehabilitation

Long-term rehabilitation is a mixture of therapeutic and problem-solving approaches to limit and adapt to the impact of stroke's brain damage on daily life.

Discharge from hospital is primarily determined by level of support at a patient's home. It does not necessarily signify maximum recovery has occurred, and accordingly, 'transfer of care' is perhaps a more apt description which highlights the need for continuing contact with rehab services (Young and Forster, 2007).

Population studes have shown the time to reach best functional performance for mild, moderate, and severe strokes to be 8, 13, and 17 weeks, respectively, though of course times can vary considerably for individual patients (Jorgensen et al, 1995).

Strokes cause sigificant needs for care, with up to 74% of patients requiring help with ADLs. It is important to equip and support caregivers in the community, and practical training programmes decrease burden, anxiety, and depression among caregivers while reducing costs (Patel et al, 2004).

Transferring care to the home earlier rather than later, and providing follow-up specialist services, reduces death or dependency and prevents deterioration (Young and Forster, 2007).

Family doctors play an important role in stroke prevention, education, early detection, and long-term treatment. Their interactions with the stroke team can provide valuable information for all members of the health care team, especially as transfer of care is underway.

Secondary Prevention

Early post-stroke VTE prophykaxis includes:

- early mobilization

- adequate hydration

- compression stockings

- optimized antiplatelet use: ASA or heparin

- anticoagulation for higher risk patients

Carotid Endarterectomy should be done within 2 weeks after an ipsilateral carotid sichemic stroke. Carotid stenting is an option for those who cannot go through endarterectomy.

Lower cholesterol, thin blood, and give anti thrombotics

- avoid combination ASA and clopidogrel

Consequences and Course

- early events

- mortality

- complications

- recurrence

Early Events

Clinical outcomes depend on disease severity. In mild cases, a transient postischemic confusion state can be followed by complete recovery. In other cases, even with mild global ischemia, severe, irreversible damage can result.

About 1/4 of patients worsen during the first 24-48 hours.

A third of patients with hemorrhagic stroke can have rapid expansion of the hematoma within a few hours.

Mortality

About 1/4 of patients with stroke die within a month, about 1/3 by 6 months, and 1/2 by one year (Hankey et al, 2000). The outcomes are even worse for hemorrhagic stroke, with one-month survival around 50%. The major cause of early death is neurological deterioration, with complications such as aspiration or infection important as well. Later deaths are commonly cardiac or complications of stroke.

Anterior circulation syndromes have a poorer prognosis than other types, with lacunar syndromes having the best outcomes.

The best predictors of recovery at 3 months are initial neurological deficit and age. Other factors include high blood glucose, body temperature, and previous stroke.

Complications

With focal cerebrovascular disease, outcomes depend on the area of brain affected, and can evolve over time, with a degree of slow improvement occurring over months.

Neurologic complications include:

- cerebral edema

- seizures

- hemorrhagic transformation of infarct

- neurological deficits: sensory, motor, blindness, aphasia, other.

A stroke is not simply a brain disease. It affects the whole person and the family. Non-neurological complications include:

- MI

- arrhythmia

- aspiration/pneumonia

- DVT/PE

- malnutrition

- pressure sores

- orthopedic complications

- contractures

- depression, both in survivors and caregivers

Common problems include social isolation, restricted participation in leisure activities, delayed return to work, anxiety, and depression (Young and Forster, 2007). Common information needs include:

- causes and risk factors of stroke

- availablity of local services and support groups

- financial advice

- guidance on driving and transport

- medication and secondary prevention

- understanding of the care plan

- advice on returning to work and participation in leisure activities

- discussion of sexual issues

There are a number of excellent patient and family resources on stroke:

Recurrence

Risk of recurrence can be guided by the ABCD2 score.

A score of 4 or more justifies urgent evaluation, treatment, or observation, as 30-day stroke risk can be 5-15% (Johnston et al, 2007).

feature |

points |

age 60 or older |

1 |

blood pressure on first assessment >140 mmHg systolic, >90 mmHg diastolic |

1 |

clinical features of TIA

|

2 |

duration of TIA

|

|

diabetes |

1 |

Diffusion-weighted MRI or MRA can identify occluded vessels and increased risk of recurrence.

Resources and References

http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/179/12/S1

Brain Attack Coalition www.stroke-site.org

NHS Health Technology Assessment Study

Am Family Physician, 2009.

ACTIVE investigators. 2009. Effect of Clopidogrel Added to Aspirin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. NEJM. April...

Cadilhac DA et al. 2004. Multicenter comparison of processes of care between stroke units and conventional care wards in Australia. Stroke. 35:1035-40.

Donnan GA, Fisher M, Macleod M, and David SM. 2008. Stroke. Lancet.

Goldstein LB et al. 2006. Primary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 37: 1583-1633.

Gilligan AK et al. 2005. Stroke units, tissue plasminogen activator...

Hankey GJ et al. 2000. Five-year survival....

Johnston SC et al. 2007. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Lancet. 369:283-92.

Jorgensen H et al. 1995. Outcome and time course of recovery in stroke. Part II: Time course of recovery. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 76(5):406-12.

Kidwell C et al. 1999. Diffusion MRI in patients with transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 30:1174-80.

Lopez AD et al. 2006. Global and regional...

Patel A et al. 2004. Training care givers of stroke patients: economic evaluation. BMJ. 328(7448):1102.

Phillips SJ, Eskes GA, Gubitz GJ. 2002. Description and evaluation of an acute stroke unit. CMAJ. 167(6):655-60.

Pollock A et al. 2007. Physiotherapy treatment approaches for the recovery of postural control and lower limb function following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):CD001920.

Strong K, Mathers C, Bonita R. 2007.

Thrift AG, Donnan GA, and McNeil JJ. 1995.

Van Peppen RPS et al. 2004. The impact of physical therapy on functional outcomes after stroke: what's the evidence? Clin. Rehabil. 18(8):833-62.

World Health Organization, 2000. The World Health Report 2000. Geneva, WHO.

Young J, Forster A. 2007. Rehabilitation after stroke. BMJ. 334:86-90.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly: book and film by Jean-Dominique Bauby, who suffered a stroke leaving him with locked-in syndrome.

Topic Development

authors:

reviewers: