Meningitis

last authored: April 2012, Dave LaPierre

last reviewed:

Introduction

Meningitis is an inflammation of the brain meninges. It can be infectious or non-infectious, the latter being caused by other sources of inflammation

Meningitis occurs at a peak age of 6-12 months, and 75% of cases occur in those under 15 years of age (ref).

Central nervous system (CNS) infections can range from rapidly fatal to chronic, and effective diagnosis and treatment is crucial for outcomes. The need to start antibiotics for bacterial meningitis is balanced with the risk of performing lumbar puncture before ruling out mass lesions.

Patients typically experience fever, headache, altered mental status, seizures, focal neurological signs, and stiff neck.

The Case of...

a simple case introducing clincial presentation and calling for a differential diagnosis. To get students thinking.

Causes and Risk Factors

Infectious meningitis can be considered acute, subacute/chronic, or aseptic.

Acute meningitis affecting different ages can be caused by different pathogens.

0-3 months

|

3 months-3 years

|

children and adolescents

|

adults

|

Asceptic meningitis is most commonly caused by:

|

Subacute and chronic meningitis can be caused by:

|

Infectious causes in special populations include:

- nosocomial: S aureus, Staph epidermidis, aerobic GNB (including Pseudomonas)

- basilar skull fracture: S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, group A strep

The most common non-infectious causes include:

- subarachnoid hemorrhage

- cancer

- sarcoidosis

Risk factors include:

- immunocompromised (S pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, L monocytogenes, aerobic gram-negative rods, CMV, EBV)

- neuroanatomical defects (surgery, skull fracture)

- parameningeal infection (sinusitis, mastoiditis, orbital cellulitis)

- environmental (sick contacts, day care)

- nosocomial meningitis: procedures and devices

Pathophysiology

Meningitis often follows transient colonization of the pharynx or oropharynx. This can lead to bacteremia or pneumonia, as well as to direct spread into nasal sinuses or mastoids. In adults, the latter is more common. Seeding of the meninges follows endothelial cell injury.

With N. meningitidis, epithelial invasion is facilitated by pili and by IgA protease. Subepithelial multiplication is followed by bacteremia and crossing the blood-brain barrier, likely mediated by capsule polysaccharide.

Gram-negative meningitis occurs in the very ill, or in those who have entry to the meninges, through trauma, surgery, or tumour.

Aseptic meningitis is most frequently caused by viruses following systemic viremia.

Tuberculosis can cause meningitis following rupture of a focus into the subarachnoid space. Vasculitis can follow inflammatory exudate which surrounds brain vasculature, leading to ischemia.

Mental status changes are related to raised ICP. Bacterial toxicity is implicated in cochlear and neuronal daamge, while pathogens and host activity damage tissue.

The subarachnoid space is unique in that it lacks fully-organized drainage and also does not allow blood cells. However, macrophages are present. Activated neutrophils are recruited when large numbers of bacteria are present.

Signs and Symptoms

Meningitis can quickly make patients very sick and lead to permanent disability or death. A high suspicion is required for health care providers in approaching a person who is unwell.

An absence of the classic triad eliminates a diagnosis of ABM: fever, nuchal regidity, or altered mental status.

- history

- physical exam

History

CNS symptoms will often will be proceded by an upper respiratory tract infection, or can occur spontaneously, with abrupt or gradual onset.

Common symptoms of bacterial meningitis include:

- headache

- fever, lethargy, irritability, photophobia, headache

- stiff/sore neck (absent in 1/2 of patients)

- nausea/vomiting

- seizures (20%)

Infants may show poor feeding, irritablity, lethargy.

Inquire into a relevant exposure history

- tuberculosis

- HIV

- ticks (Lyme disease)

- travel: Ohio, Mississippi River Valleys (fungal infections); malaria

Viral meningitis can cause:

- acute onset, severe, headache, worse with sitting, standing, coughing

- fever

- photophobia

- meningismus

Physical Exam

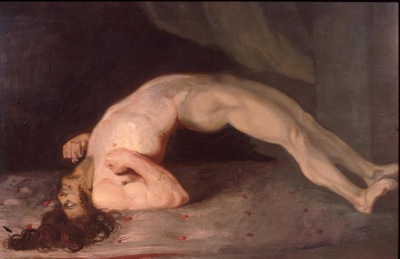

Sir Charles Bell - Opisthotonos 1809 (source)

Signs include:

- nuchal rigidity

- jolt accentuation of headache

- Brudzinski's sign: reflex hip/knee flexion upon active flexion of neck

- Kernig's sign: reflex contraction and pain in hamstrings with leg extension during hip flexion

- opisthotonos: body-wide spasm, in which head and heels bent backward

Signs of increased intracranial pressure include:

- ptosis

- CN VI palsy

- dilated, poorly reactive pupils

- bradycardia and hypertension (Cushing's reflex)

- apnea

- papilledema

petechial or purpural rash is associated with meningococcus and with poor prognosis

Investigations

- lab investigations

- lumbar puncture

- diagnostic imaging

Lab Investigations

Bloodwork should include:

- CBC and differential

- electrolytes

- creatinine, BUN

- blood glucose

- blood cultures

Based on possible agents, testing should be considered for:

- HIV testing should be offered to explore the possibility of immunodeficiency, or acute viral infection.

- syphilis

- cryptococcal antigen

- fungal culture

- Borrelia burgdorferi

- Histoplasma capsulatum

- tuberculosis (AFB, culture)

- viruses: PCR

Latex agglutination test can be used, but is not routinely done.

Lumbar puncture

There should be a low threshold of suspicion for meningitis, prompting consideration of lumbar puncture.

LP is urgently required, though should be preceded by a CT to rule out mass lesion if:

- papilledema

- focal neurological deficits

- unilateral headache

- history is subacute (weeks or months)

- seizures

- loss of consciousness

LP can reveal:

- increased opening pressure

- cloudy CSF with bacterial infection

- exam for WBC, protein, glucose, Gram stain, C&S, latex agglutination test, Ziehl-Neilson stain for TB

Even in situations where antibiotics are started before LP, CSF analysis can reveal gram stain, neutrophilia, and hypogluchorachia.

cause |

cells (per ml) |

neutrophils |

glucose |

protein (mg/dL) |

bacterial |

500-10,000 |

>90% |

low |

>150 |

aseptic |

10-200 |

early >50%; late <20% |

normal |

>100 |

HSV |

0-1000 |

>50% |

normal |

<100 |

tuberculosis |

50-500 |

early >50%; late <50% |

low |

>150 |

syphilis |

50-500 |

<10% |

low |

<100 |

Other findings can include:

- mononucleocytosis can be seen in meningitis caused by Listeria, tuberculosis, and syphilis.

- India ink preparation can reveal cryptococcus (encapsulated yeasts).

If evaluation is not possible, as can occur with a comatose patient, or if CT is unavailable, lumbar puncture should be deferred. Instead, blood and throat culture should be done and antiobiotic therapy started.

Diagnostic Imaging

Head CT should be done prior to lumbar puncture if the preceding signs or symptoms are present. This is to exclude a mass lesion, which can lead to brain herniation, even in the absence of papilledema.

However, CT doesn't aid in diagnosis.

Mixed infections, or those caused by unusual pathogens, should prompt imaging of the sinuses and mastoids to evaluate these areas as a source of infection.

Differential Diagnosis

Meningitis can be caused by non-infectious causes, such as medications.

Other differential diagnoses of headache, altered level of consciousness, and systemic illness, include:

- meningeal carcinomatosis (metastatic adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, melanoma)

- sarcoidosis

- CNS vasculitis

- stroke (esp SAH)

- drugs

- carcinomatosis

- encephalitis

- sinusitis

- ruptured brain abscess

- infective endocarditis

- sepsis

Treatments

Meningitis is a medical emergency, and treatment should be started within 60 minutes.

Emperic bacterial therapy: vancomycin + cefotaxime, or aminoglycoside + cefotaxime if gram-negative bacetria are suspected.

If patients are older than 50, or immunocompromised, ampicillin + vancomycin + ceftriaxone/cefotaxime should be used.

If the CSF gram stain shows Pneumococcus or Meningiococcus, Penicillin G or a third-generation cephalosporin should be started. Vancomycin should be added until susceptibility testing is returned.

Viral meningitis: supportive + acyclovir for HSV

Monitor glucose, acid-base, and hydration status.

Anticonvulsants may be used as needed to address seizures.

Steroids are indicated for Pneumococcal or Hemophilus meningitis; empiric treatment should be given before (10-20 min) antibiotics to prevent hyperimmune response following cell death. However, evidence is varying.

Prophylaxis

Patients should be isolated until 24 hours after initiation of culture-sensitive antiobiotics. This is especially important for Neisseria and for Hemophilus, given how aggressive they can be.

Prophylaxis is recommended for contacts; rifampin is frequently used. Warn patients of orange tears and urine, and that oral contraceptives will be temporarily ineffective.

vaccination

main article: vaccination

H.influenza type b (Hib) vaccine series should be offered to all people.

Meningococcal vaccine should be given in patents with splenectomy, complement deficiency, or in circumstances of outbreaks. The vaccine is also becoming routine in some places.

The pneumococcal vaccine should be given to the elderly, those with chronic disease, the immunocompromised, or patients with splenectomy.

Consequences and Course

Approximately 30% of adults die of bacterial meningitis. Deafness and other neurological deficits are common in those who survive.

Prognosis is poorer with increase extent of CNS damage and decreases in consciousness.

Additional Resources

Topic Development

authors:

reviewers: