Gallstone Disease

last authored: Dec, 2011, Jeremy Springer

last reviewed: March 2012, Dr Brock Vair

Introduction

Gallstone disease is one of the most common diseases associated with the gastro-intestinal system (27) and accounts for a large proportion of elective abdominal surgical procedures. Fortunately, the overall mortality rate associated with gallstone disease is 0.6% (30). Gallstone formation in the gall bladder can result from many different disorders and is referred to as cholelithiasis.

Up to 20% of the North American and European adult population has gallstones (15), with an increased prevalence in women compared to men (43). The majority of individuals with gallstones are asymptomatic and do not require medical intervention (2). There is a higher incidence of gallstone disease in Western countries and individuals from northern European descent, Hispanic and Native American populations (29).

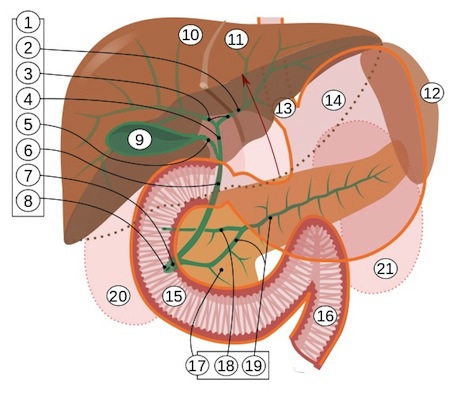

As gallstones aggregate and grow over time there are risks that the stone will migrate and impact in the biliary system (Fig. 1), which can produce the following complications of gallstone disease:

- acute biliary pain

- cholecystitis – gallbladder inflammation/infection

- choledocholithiasis – common bile duct obstruction

- bacterial cholangitis – common bile duct inflammation/infection

- acute pancreatitis (40) – pancreatic duct obstruction triggering activation of pancreatic enzymes and pancreatic inflammation.

- Bouveret syndrome – duodenal obstruction caused by the gallstone eroding through the gallbladder wall causing a cholecystoenteric fistula

- Mirizzi syndrome – compression of the common hepatic duct caused by gallstone obstructing the cystic duct (10)

Most of the 10-15% of adults with gallstones have no symptoms, with only 1-3% of people developing pain or other symptoms. As many as 40% of people with general anaesthesia and surgery with asymptomatic gallstones can become symptomatic within 6 weeks.

Contraction of the gallbladder during transient cystic obstruction can cause biliary colic. Persistent obstruction of the cystic duct leads to superimposed inflammation or infection (acute cholecystitis). Distal duct obstruction can lead to abdominal pain, cholangitis, or pancreatitis.

The Case of Mary-Anne R

Mary-Anne R is 36-year-old woman with a BMI of 31. She has type 1 diabetes and hypertension controlled with medication. While driving home one day, she began to feel unwell and noted a steady, severe pain in the right upper quadrant of her abdomen. She developed a temperature of 39.5°C and a fast heart rate.

Upon presentation to the local ER, physical examination revealed a positive Murphy’s Sign (tender abdomen in the region of the gallbladder upon palpation during inspiration). Laboratory examination revealed leukocytosis and ultrasonography revealed the presence of gallstones and gallbladder wall thickening (greater than 4-5mm). The ER physician prescribed narcotic analgesia and referred the patient to general surgery the next morning.

Causes and Risk Factors

The following section will briefly discuss the major risk factors for developing gallstone disease:

Sex: Gallstones are 2-3 times more common in women, especially during the childbearing years. Pregnancy also increases the risk of developing gallstones, especially in recurrent pregnancies (39). Sex hormones are most likely responsible for the increased risk (17, 21).

Age: The risk of gallstone disease increases with age. Presumably, aging causes cholesterol secretion to increase, resulting in the formation of lithogenic bile and increasing the likelihood of stone formation (41).

Obesity: gallstone formation is associated with obesity (BMI>30) due to increased cholesterol secretion into the bile (1, 29, 38).

Family History/Genetics: Data suggest that genetic factors are responsible for at least 30% of symptomatic gallstone disease (19, 33), however this is likely an underestimate due to lack of standardization with reporting.

Diabetes: patients with type 2 diabetes have increased risk of hyperlipidemia, obesity and gallbladder hypomotility. Specifically, these patients are at higher risk of gallstone formation and acute pancreatitis (20).

Diet: Poor quality diets in both men and women such as low-fiber, high carbohydrate and high fat diets have been associated with gallstone formation and subsequent symptomatic gallstone disease (32, 36, 37). The association with diet is likely the underlying reason why Western society experience increased prevalence of gallstone disease compared to Eastern society.

Lithogenic Bile: Bile is primarily composed of a mixture of bile salts, phospholipids, unesterified cholesterol and bilirubin conjugates referred to as lipopigments. For numerous reasons, some individuals have a disruption in the normal bile component ratio. Specifically, they have a higher concentration of cholesterol relative to either bile salts or phospholipid. This state of bile is referred to as lithogenic bile and has an icreased tendency to form gallstones (when the appropriate nucleating factors are present) (42).

Pathophysiology

There are 2 major types of gallstones, which are classified based on their composition.

1. Cholesterol gallstones account for approximately 90% of all gallstones and form as a result of hypersecretion of cholesterol, gallbladder hypo-motility and the accumulation of mucin gel (6, 7). Other nucelating agents can include bacteria, antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, TPN, and blood transfusions.

2. Pigment stones account for the remainder of all cases and are classified as black pigment stones which form as a result of precipitation of calcium hydrogen bilirubinate and associated inorganic salts, phosphate and calcium bicarbonate (7). The second class of pigment stones are referred to as brown pigment stones and form in the bile duct due to bile stasis, parasites, and bacterial infection (7).

The complications that arise from gallstone disease are typically associated with mechanical obstruction of the ducts associated with the biliary system and the subsequent complications of inflammation, infection, and ischemic damage. The following section will briefly discuss the pathophysiology of the various clinical entities associated with gallstone formation.

Acute Cholecystitis will occur in approximately 90% of individuals who suffer from symptomatic gallstones and in the majority of acute cholecystitis cases there is complete obstruction of the cystic duct (44). Once the stone is lodged in the cystic duct, there is an increase in intra-luminal pressure resulting in reduced venous and lymphatic outflow, which can cause gallbladder edema , ischemia and distention (44). If the stone does not pass spontaneously, full thickness inflammation of the gallbladder wall results with localized peritonitis and systemic illness. Perforation of the gallbladder wall can occur in as many as 10% of patients (44).

Chronic cholecystitis is considered a chronic inflammation of the gallbladder caused by the repeated occurrence of mild attacks of cholecystitis. Generally fibrosis occurs in the gallbladder wall and mucosal atrophy occurs in this region as well (14).

Choledocholithiasis occurs when gallstones pass through the cystic duct and become lodged in the common bile duct. Choledocholithiasis will occur in 15% of patients with gallbladder stones (16).

Acute cholangitis occurs when infection occurs in the biliary system, as a result of obstruction and subsequent bacterial colonization (16). Cholangitis is considered uncommon, and occurs in about 1% of cases of cholelithiasis (4). The majority of bacterial infections are polymicrobial and the most abundant species is typically E. coli (4).

Acute Biliary Pancreatitis (ABP) Pancreatitis is most commonly caused by gallstones . Chronic alcohol use is the second most common cause. Up to 60% of non-alcoholic patients with ABP have gallstones. It is generally defined as an inflammatory condition of the pancreas that can be caused by numerous factors and can range from mild to fatal (28). Numerous hypotheses including the Opie hypothesis have been proposed to explain the relationship between gallstone disease and pancreatitis. Initially , a gallstone may impact within the common channel at the duodenal papilla causing the flow of bile into the pancreatic duct resulting in inappropriate activation of proteolytic enzymes and pancreatitis (Fig. 1). Alternatively, a gallstone could produce obstruction of the pancreatic duct, increasing the intraductal pressure leading to cellular death and pancreatitis (13, 16, 22, 23).

Gallstone Ileus This is actually a mechanical obstruction of the intestine that occurs when a large gallstone erodes through the gallbladder wall into the small intestine, creating a fistula between the gallbladder and typically the duodenum (16). The gallstone travels through the small intestine and eventually obstructs the lumen of the intestine, typically the distal ileum (16).

Signs and Symptoms

About one half of all people remain asymptomatic, one third develop biliary colic or chronic cholecystitis, and 15% develop acute complications.

- history

- physical exam

History

The majority of individuals with gallstones are asymptomatic and will likely never encounter any complications throughout their lifetime (2).

Of those individuals that do encounter issues with gallstone formation, the majority will experience the signs and symptoms associated with acute biliary pain and cholecystitis (10).

These include (16, 18):

- Biliary pain - severe/steady pain in the chest, epigastrium or right upper quadrant that may radiate to the right shoulder or back. May have sudden onset, with plateau after a few minutes, and subsiding over minutes-hours

- Nausea + vomiting

- Jaundice (associated with cholecystitis , Mirizzi’s syndrome or common bile duct stones)

- Fever

- Anorexia

- Light coloured stool/tea coloured urine (accompanying jaundice)

30% of patients with acute cholangitis will experience Charcot’s triad, which consists of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever/chills and jaundice (4, 18).

Patient with pain secondary to choledocholithiasis commonly have pain similar to biliary pain of gallbladder origin. The pain can be intermittent as a result of transient blockage of the bile duct or more severe and steady associated with a complete blockage (16).

Patients experiencing acute cholangitis will present with similar symptoms to cholecystitis and may experience symptoms associated with Charcot’s Triad (4, 18).

If acute cholangitis is not treated, the condition can progress into acute suppurative cholangitis, which is characterized by the presence of purulent material in the biliary system. Suppurative cholangitis is accompanied by hypotension and mental confusion along with the three components of Charcot’s triad, collectively referred to as Reynold’s pentad (16, 18, 25). Additionally, untreated cholangitis may lead to systemic sepsis and death or the formation of liver abscesses.

Physical Exam

Vital signs: fever and tachycardia can be present, suggesting infection. Tachycardia, in concert with decreased blood pressure, suggests significant disease and the development of shock.

Jaundice may be noted if biliary tree blockade is occurring.

Abdominal exam can reveal right upper quadrant tenderness, especially with inspiration, (Murphy’s sign) and guarding (31). An abdominal mass may also be present in the right upper quadrant.

Investigations

- lab investigations

- diagnostic imaging

Lab Investigations

The lab results for acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis and choledocholithiasis are relatively similar (16).

There are 2 typical patterns of enzyme abnormalities in hepato-biliary disease:

1. Obstructive pattern – significant elevation of conjugated bilirubin/GGT and Alkaline Phosphatase with minimal elevation of ALT/AST.

2. Hepatocellular pattern – significant elevation of ALT/AST. Minimal elevation of conjugated bilirubin/GGT/AP.

CBC/Differential: left shifted leukocytosis

Serum amylase and lipase: suggesting acute cholecystitis or pancreatitis. Patients with acute biliary pancreatitis often present with significantly higher serum amylase and lipase levels compared to pancreatitis caused by alcohol use (16).

ESR or CRP

Diagnostic Imaging

Lab investigations and physical exam are essential components to the diagnosis of cholecystitis or any biliary pathology, however the use of diagnostic imaging tools are essential in obtaining a precise diagnosis (35).

The following imaging studies have been indicated for gallstone disease diagnosis and will be briefly discussed:

- Ultrasonography (US) – a noninvasive technique that when completed by a trained user can diagnose cholelithiasis with 96% accuracy, 98% sensitivity and 93.5-97.7% specificity (8). Using US, gallbladder wall thickening ( > 2mm ) can be detected ,providing evidence of acute or chronic inflammation. During US, a positive Murphy’s test can also be elicited using the US transducer (16).

- Cholescintigraphy (HIDA scan) – is indicated if US is inconclusive and no diagnosis has been made (5). This method requires the IV injection of technetium labeled hepatic iminodiacetic acid, which is taken up specifically by hepatic cells and secreted in bile. This dye is visualized in the gallbladder if the cystic duct is patent. Non-visualization of the gallbladder suggests cystic duct obstruction and is considered a positive test. This test has a sensitivity of approximately 97% and a specificity of approximately 90% (12).

- CT Scan – can be useful in the diagnosis of cholecystitis and related gallstone disease. Gallbladder wall thickening, distension, high-attenuation bile, and subserosal edema can all be visualized and used in diagnosis (11). However gallstones are detected less reliably than with US .

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) – If imaging demonstrates stones within the extrahepatic biliary tree ERCP is used for therapeutic intervention. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla followed by basket or balloon extraction of stones is an effective means to clear the biliary tree of stones and avoids general anesthesia and abdominal surgery. However ERCP is invasive and is associated with a ~1% mortality rate resulting from pancreatitis , duodenal perforation , sepsis and bleeding.

- Magnetic Resonance may be useful in diagnosis in patients who are pregnant and complaining of abdominal pain, or if other diagnostic tools are unavailable (34).

- X-Ray Radiographs – are useful in diagnosing small bowel obstructions but are not specific for gallstone ileus unless air in the biliary tract is visualized. X-ray may be less accurate for visualizing gallstones in the biliary tract as a large proportion of gallstones are radiolucent (3).

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of gallstone disease and the numerous complications associated with gallstones in patients experiencing abdominal symptoms is challenging. Initially, the physician should identify if acute biliary pain is responsible for symptoms. Biliary pain is usually constant pain, sometimes associated with the recent ingestion of high fat foods and is caused by gallbladder obstruction. The following list briefly identifies some major diseases presenting with symptoms similar to gallstone disease (16).

- Gallbladder polyps

- Gallbladder/pancreas/bile duct adenomas/carcinomas

- Acute appendicitis

- Penetrating or perforated peptic ulcer

- GERD

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Acute mesenteric ischemia

- Right renal calculi

Treatments

Asymptomatic people should be followed expectantly.

Surgery

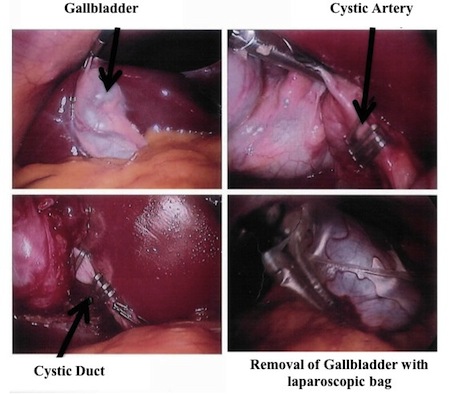

Once a patient develops symptoms associated with gallstone disease it is generally agreed that early cholecystectomy is indicated due to a strong likelihood of persistent or recurrent symptoms. Urgent cholecystectomy does not carry a higher morbidity or mortality risk compared to delayed operation (24). Cholecystectomy can be performed laparoscopically, which is generally tolerated better and associated with less post-operative complications. During a cholecystectomy an intraoperative cholangiogram (ERCP) may be indicated if there is suspected biliary duct stones (16).

In patients experiencing acute cholecystitis in whom cholecystectomy is contra-indicated due to co-morbidities, cholecystostomy (percutaneous drainage of gallbladder contents) may be indicated until the patient can safely undergo surgery (16).

Pain control

Narcotic analgesics are also often used in cases where surgery may be delayed or if an observation period is required.

Adjuvants

Anti-emetics, such as dimenhydramine, can be used to treat the nausea and vomiting that commonly accompanies gallstone disease.

Consequences and Course

Removal of the gallbladder and associated gallstones is a generally a well-tolerated operation with low morbidity and mortality. It will reliably result in a resolution of abdominal pain due to gallstone disease. There are numerous rare post-operative complications that can occur such as wound infection, subhepatic or subphrenic abscess, bile peritonitis, post-operative hemorrhage or common bile duct injury (16).

Resources and References

1. Amaral JF, Thompson WR. Gallbladder disease in the morbidly obese. The American journal of surgery 149: 551-557, 1985.

2. Attili AF et al. Epidemiology of gallstone disease in Italy: prevalence data of the Multicenter Italian Study on Cholelithiasis (M.I.COL.). Am J Epidemiol 141: 158-165, 1995.

3. Bell GD, Dowling RH, Whitney B, Sutor DJ. The value of radiology in predicting gallstone type when selecting patients for medical treatment. Gut 16: 359-364, 1975.

4. Boey JH, Way LW. Acute cholangitis. Ann Surg 191: 264-270, 1980.

5. Bortoff GA, Chen MY, Ott DJ, Wolfman NT, Routh WD. Gallbladder stones: imaging and intervention. Radiographics 20: 751-766, 2000.

6. Carey MC. Pathogenesis of gallstones. Am J Surg 165: 410-419, 1993.

7. Conte D, Fraquelli M, Giunta M, Conti CB. Gallstones and liver disease: an overview. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 20: 9-11, 2011.

8. Cooperberg PL, Burhenne HJ. Real-time ultrasonography. Diagnostic technique of choice in calculous gallbladder disease. N Engl J Med 302: 1277-1279, 1980.

9. Diehl AK. Epidemiology and natural history of gallstone disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 20: 1-19, 1991.

10. Erben Y, Benavente-Chenhalls LA, Donohue JM, Que FG, Kendrick ML, Reid-Lombardo KM, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM. Diagnosis and treatment of Mirizzi syndrome: 23-year Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Coll Surg 213: 114-9; discussion 120-1, 2011.

11. Fidler J, Paulson EK, Layfield L. CT evaluation of acute cholecystitis: findings and usefulness in diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 166: 1085-1088, 1996.

12. Fink-Bennett D, Freitas JE, Ripley SD, Bree RL. The sensitivity of hepatobiliary imaging and real-time ultrasonography in the detection of acute cholecystitis. Arch Surg 120: 904-906, 1985.

13. Forsmark CE. Pancreatitis and its complications. Humana Pr Inc, 2005.

14. Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Hirata K, Sekimoto M, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Wada K, Miura F, Yasuda H, Yamashita Y, Nagino M, Hirota M, Tanaka A, Tsuyuguchi T, Strasberg SM, Gadacz TR. Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14: 15-26, 2007.

15. Kratzer W, Mason RA, Kächele V. Prevalence of gallstones in sonographic surveys worldwide. J Clin Ultrasound 27: 1-7, 1999.

16. Lawrence PF. Essentials of general surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

17. Maurer KR, Everhart JE, Ezzati TM, Johannes RS, Knowler WC, Larson DL, Sanders R, Shawker TH, Roth HP. Prevalence of gallstone disease in Hispanic populations in the United States. Gastroenterology 96: 487, 1989.

18. Miura F, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Wada K, Hirota M, Nagino M, Tsuyuguchi T, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Belghiti J, de Santibanes E, Gadacz TR, Gouma DJ, Fan ST, Chen MF, Padbury RT, Bornman PC, Kim SW, Liau KH, Belli G, Dervenis C. Flowcharts for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14: 27-34, 2007.

19. Nakeeb A, Comuzzie AG, Martin L, Sonnenberg GE, Swartz-Basile D, Kissebah AH, Pitt HA. Gallstones: genetics versus environment. Ann Surg 235: 842, 2002.

20. Noel RA, Braun DK, Patterson RE, Bloomgren GL. Increased risk of acute pancreatitis and biliary disease observed in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 32: 834-838, 2009.

21. Novacek G. Gender and gallstone disease. WMW Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 156: 527-533, 2006.

22. Opie EL. The etiology of acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis. Transactions of the Association of American Physicians 1: 314, 1901.

23. Opie EL. The relation of cholelithiasis to disease of the pancreas and to fat necrosis. Am J Med Sci 121: 27-43, 1901.

24. Papi C, Catarci M, D'Ambrosio L, Gili L, Koch M, Grassi GB, Capurso L. Timing of cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 99: 147-155, 2004.

25. Reynolds BM, Dargan EL. Acute obstructive cholangitis: A distinct clinical syndrome. Ann Surg 150: 299, 1959.

26. Rossi D, Khan U, McNatt S, Vaughan R. Bouveret syndrome: a case report. W V Med J 106: 18-22, 2010.

27. Russo MW, Wei JT, Thiny MT, Gangarosa LM, Brown A, Ringel Y, Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Digestive and liver diseases statistics, 2004. Gastroenterology 126: 1448-1453, 2004.

28. Sakorafas GH, Tsiotou AG. Etiology and pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis: current concepts. Journal of clinical gastroenterology 30: 343, 2000.

29. Shaffer EA. Epidemiology and risk factors for gallstone disease: has the paradigm changed in the 21st century? Curr Gastroenterol Rep 7: 132-140, 2005.

30. Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder stone disease. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 20: 981-996, 2006.

31. Singer AJ, McCracken G, Henry MC, Thode HC, Cabahug CJ. Correlation among clinical, laboratory, and hepatobiliary scanning findings in patients with suspected acute cholecystitis. Ann Emerg Med 28: 267-272, 1996.

32. Stokes CS, Krawczyk M, Lammert F. Gallstones: environment, lifestyle and genes. Dig Dis 29: 191-201, 2011.

33. Tirziu S, Bel S, Bondor CI, Acalovschi M. Risk factors for gallstone disease in patients with gallstones having gallstone heredity. A case-control study. Rom J Intern Med 46: 223-228, 2008.

34. Tkacz JN, Anderson SA, Soto J. MR imaging in gastrointestinal emergencies. Radiographics 29: 1767-1780, 2009.

35. Trowbridge RL, Rutkowski NK, Shojania KG. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association 289: 80, 2003.

36. Tsai CJ, Leitzmann MF, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Dietary carbohydrates and glycaemic load and the incidence of symptomatic gall stone disease in men. Gut 54: 823-828, 2005.

37. Tsai CJ, Leitzmann MF, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Glycemic load, glycemic index, and carbohydrate intake in relation to risk of cholecystectomy in women. Gastroenterology 129: 105-112, 2005.

38. Tsai CJ, Leitzmann MF, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Central adiposity, regional fat distribution, and the risk of cholecystectomy in women. Gut 55: 708-714, 2006.

39. Valdivieso V, Covarrubias C, Siegel F, Cruz F. Pregnancy and cholelithiasis: pathogenesis and natural course of gallstones diagnosed in early puerperium. Hepatology 17: 1-4, 1993.

40. Venneman NG, Buskens E, Besselink MG, Stads S, Go PM, Bosscha K, van Berge-Henegouwen GP, van Erpecum KJ. Small gallstones are associated with increased risk of acute pancreatitis: potential benefits of prophylactic cholecystectomy? Am J Gastroenterol 100: 2540-2550, 2005.

41. Völzke H, Baumeister SE, Alte D, Hoffmann W, Schwahn C, Simon P, John U, Lerch MM. Independent risk factors for gallstone formation in a region with high cholelithiasis prevalence. Digestion 71: 97-105, 2005.

42. Wang DQH, Cohen DE, Carey MC. Biliary lipids and cholesterol gallstone disease. Journal of lipid research 50: S406-S411, 2009.

43. Wang HH, Liu M, Clegg DJ, Portincasa P, Wang DQ. New insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying effects of estrogen on cholesterol gallstone formation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1791: 1037-1047, 2009.

44. Ziessman HA. Acute cholecystitis, biliary obstruction, and biliary leakage. Semin Nucl Med 33: 279-296, 2003.

Topic Development

authors:

reviewers: